Recently I was prompted to ponder whether angels have beards. I was visiting St John’s church at Howsham, in the Harton Benefice, north east of York. In the church’s porch is a carving of an angel sporting a beard (below). It was a sight that stimulated thoughts about angels, our tendency to anthropomorphise these heavenly beings, and what our long history says, across many faiths, about angels in the 21st century. As it happens, the appearance of angels has a lot to do with our imagination and how people conceived of beings who can span the divide between the secular and the sacred.

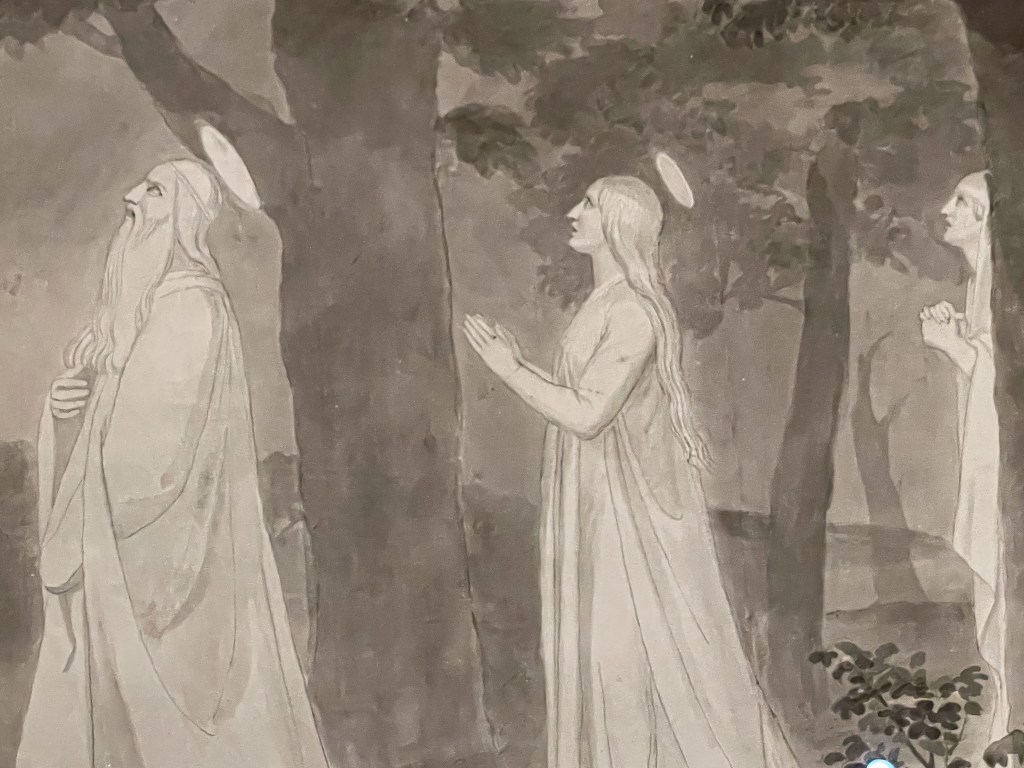

Today, on the Feast of St Michael and All Angels, it might be helpful to recall that many theologians across church history have not viewed angels as corporeal. Instead they have been regarded as expressions of Divine thought and agency; the light of heaven that breaks into the darkness of this world. Of course, in the history of art they are consistently represented as beings akin to people, albeit extra-shiny and with a pair of wings. Their expressions are typically impassive, like good servants they betray neither joy nor sorrow about the news being conveyed. The notable exception to this is the antics of the heavenly host at the Incarnation, joyfully praising God and generally whooping it up.

Thomas Aquinas, the Angelic Doctor, famously wrote of the “Bread of Angels, made the bread of people”. Panis angelicus is a stirring hymn of praise to God for the grace of sharing with humanity food which is the everyday fare of heaven. Consequently, at the Eucharist, angels are always referenced in the liturgy. As bread and wine are taken and consecrated, the material becomes one with the Divine, just as it did when the Word became flesh. This enacts a significant truth of Christianity: that in Christ the world is being redeemed. It is a central tenet of orthodox Christology, expressed in the Athanasian creed, that Jesus was perfectly divine and perfectly human. This was not God and a man sharing a room! The presence and witness of the angels in the liturgy expresses this fulfilment of the secular in the sacred. In the birth, death and resurrection of Christ, humanity is truly “ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven”.

“The beast taken” Revelation 19:20. York Minster Great East Window

Angels are not beings confined to churches and places of worship. The biblical references to them are most often in the secular, encountering people out in the world. Their strangeness and seemingly random appearances inspired the author of the Letter to the Hebrews to remind us that in our reception of others “some have entertained angels unawares”. During a time as poet in residence at Bradford Cathedral, Diane Pacitti published a collection of poems entitled Dark Angelic Mills. In the final entry, ‘Angels in Bradford’, Pacitti reflects that angels come in many guises. Perhaps as ‘kindertransport children, Asian workers, Syrian refugees, Rohingya Muslims’. In her poem, just as each church had its angel in the Book of Revelation, she invokes the spirit of St John to call into being the Cathedral’s angel:

Let it spread

huge-feathered wings over this hut of stone.

Let the song of wonder weave into its prayers

and seep into its silences. Angel-voice,

speaker of demanding truth, send out this church

to affirm the holy in what seems most broken.

Dark Angelic Mills by Diane Pacitti, Norwich, Canterbury Press, 2020.

The Church should always be the place which drives the heart of our participation in God’s mission of love for the world. We are drawn in, revitalised, and expelled back into the pathways that take us to both places of obvious significance, as well as to the peripheral and the neglected. In the ‘hut of stone’ where the church gathers we should encounter again the moment when the secular and the sacred meet: ‘the end of all symbols’ and the place where we are fed with the bread of angels.