A recent visit to the Auckland Project exceeded my expectations. The investment in a range of cultural, historic and artistic exhibits in this market town has been extraordinary. The excessive scale and grandeur of the Bishop of Durham’s official residence has been transformed into a visitor attraction, with a new gallery of world faiths added to the property. While the timing of the project’s opening was ill-fated, coming just months before the first lockdown in early 2020, it appears that in recent years the ambition to make the former mining town a major tourist destination has been realised.

In the episcopal residence, Auckland Castle, rooms have been themed according to many of the former bishops. This means that the furnishings are contemporaneous with the figure being celebrated, and in some cases an audio or visual loop of material is featured. For example, in remembering the controversial prelate David Jenkins, there is an extract of an interview in which he speaks about his understanding of faith and the central tenets of Christianity.

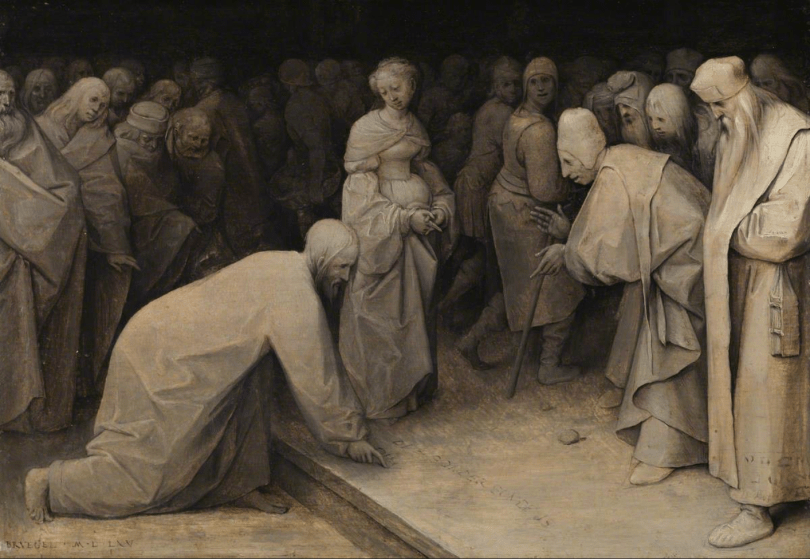

Close to the centre of Bishop Auckland, just a short walk from the Castle, there is the Spanish Gallery. Billed as “the UK’s first gallery dedicated to the art and culture of the Spanish Golden Age”, it is an impressive collection. The connection that underpins this addition to the town lies in the famous paintings which fill the walls of the Bishop’s dining room in the Castle. These are Jacob and his Twelve Sons by Francisco de Zurbarán, bought by the Bishop of Durham in 1757. It would be hard to find any collection of Spanish art in the UK, outside of London, which could compete with what has been brought together in this northern market town.

“This world class gallery, which is spread across four floors and housed in two stunning Grade II listed buildings, is fast becoming a must-see for art enthusiasts across the North East of England and beyond”.

Reflecting on both the gallery and the Castle, there is an interesting juxtaposition of inspiring artwork and the more mundane “management of religion”. Bishops have no doubt inspired many people over the centuries but, for much of the time, they have turned the wheels of religion to maintain the institution and – in the case of the Church of England – upheld the status quo. This is particularly true for the prince bishops of Durham, who often served as the State’s enforcer in the north. Such a role entitled the bishops to the magnificence of a stately home, great wealth and the other privileges of office. Some, including Bishop Westcott and David Jenkins, subverted these expectations by siding with the miners during industrial disputes. However, they appear to have been the exception rather than the rule.

“The Bishop was loudly cheered by the miners, who had assembled in large numbers in the streets of Bishop Auckland; and he has every reason to congratulate himself on the results of his intervention”.

The Spectator, “The intervention of the Bishop of Durham (Dr. Westcott) in the Durham miners’ strike” 4 June 1892

The question my visit provoked is about the relationship between the bureaucracy of faith and the creativity which often inspires and disturbs our taken-for-granted expectations. Finding them sitting so closely side-by-side at the Auckland Project was an unusual experience. When Bishop Richard Trevor bought the paintings for the Auckland Castle dining room, they were not for general viewing. This was an experience for the elite and the Castle and grounds exuded wealth and privilege. While the Auckland Project has opened up these treasures (for a reasonable price), and located them close to several narratives about previous bishops, it begs a question about the role of the Established Church. Many major works of art have been commissioned by wealthy prelates, and some of these continue to provide inspiration today, but how is a far less mighty Church maintaining its task of providing space and inspiration for wide variety of people to engage, contemplate and be changed? There was a glimmer of hope about this at the end of the faith exhibition where major works by the contemporary artist, Roger Wagner, are hung. Wagner is someone who knows how transformative art can be in the journey of faith:

“It was the first thing that brought a sense of personal connection with the Gospels – which I’d studied, but never seen that you could enter into them in that kind of way. Something art could do which I’d never envisaged before”.

Roger Wagner speaking to The Church Times in 2013.