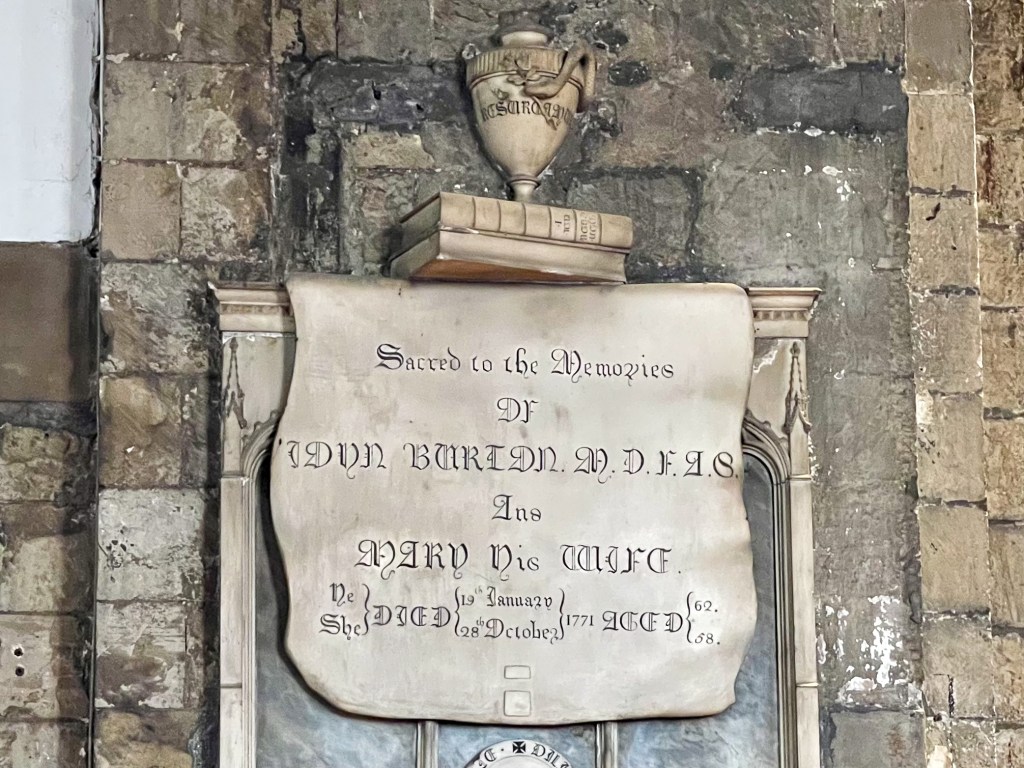

At some point during my BA studies at the University of Hull I encountered The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. I was taking a degree in English Literature and Theology, and Sterne’s renowned work cropped up in a course on Augustan Literature. It felt a disorderly work compared with other writing from the period, but its many digressions are also its captivating quality. Like a fairground roller coaster, there are hairpin bends in this fictional tour de force. Little did I imagine that a few decades later I would be living quite so close to the places Sterne would have known during his life. Near to York Minster there was Sterne’s publisher. His uncle and patron Jaques Sterne was precentor in the Minster as well as Archdeacon of Cleveland. This morning I led the service at Priory Church of Holy Trinity Micklegate, where one of the characters thought to have been lampooned in his work is buried. Dr John Burton’s pioneering work in obstetrics appears to have inspired the figure of the ‘man-midwife’, Dr Slop.

It may well be that Sterne attacked Dr Burton in this way due to the religious politics of the time. Burton was a Jacobite and Catholic sympathiser, something that landed him in goal at the instigation of the Precentor. Sterne was ordained by the time he wrote Shandy and it says something about the times that a cleric could publish something so candid about the realities of life and human follies. The novel came in at number 6 in a Guardian list of the best one hundred novels.

“Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;—they are the life, the soul of reading;—take them out of this book for instance,—you might as well take the book along with them;”

The Life and Times of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

For all the playful style of Tristram Shandy there is political weight in its portrayal of 18th century life. It is a book designed to wield influence, and in its hints and winks it would have tantalised people across a breadth of classes and situations. In an edition of In Our Time dedicated to the book, it was pointed out that the fictional writings of Sterne were seen as a way to increase the sale of his printed sermons, rather than the sermons advertising the novel. It reminds us how very different times were in Georgian England and how significant preaching was considered in this era.

While there is a lot to criticise about the way religion and politics has mixed in the past, there is also scope for concern about a church that walks away from politics. After all, politics is about the way we live – what governance permits or outlaws. It can no more be something the church should avoid than the preaching of the Gospel. The idea that Jesus wasn’t a political figure is ludicrous – in his clashes with the authorities, and teaching about the operation of institutions such as the Temple, he was entirely political.,

It has felt in recent years that the Church has had a vanishing presence in the political arena. Declining attendances combined with a focus on personal salvation have chipped away at the place the C of E once occupied. This is not the Church of Faith in the City, nor do parish clergy have the time they once enjoyed to participate extensively in civic life. Of course there’s a very good argument that laity ought to be doing this in any event, as the people of faith embedded in the community. However, the perspective of a person set aside to focus on spiritual concerns – with the experience of living and working in several communities – has a value that is unique.

Instead of providing strength, solace, inspiration, and communion, churches are decidedly human institutions comprised of the eccentric, the stupid, and the venal.

The failure of organized religion in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy by David Dobbie Tull, 1991

The recently launched Archbishops’ Commissions may be a hopeful sign that the Church wishes to speak in the public square. Given the goings-on in British politics lately, surely there is a need for a moral voice (and possibly lampooning)? What took place concerning the scrutiny of MPs suggests a political leadership that is shameless of its self-interest, only responding when its fawning supporters in the media announce that things have gone too far. Today Sterne would have ample material for a new novel, without the need for very much invention. Despite all its constraints and interested parties, the Church is called to speak from its experience, beliefs and commitment – and sometimes that speech must be stern in making clear the yawning gap between the ideals of public service, and the shameless pursuit of personal interest.