Recently I was given charge of a baby. Thankfully this was only temporary, as mum went with her older son for the start of his first day at school. We were visiting family in Scotland and I was delighted to spend a short while with this delightful child. However, it is some time since I last looked after a baby, and this level of responsibility does not come without anxiety! In my attempts to entertain the bairn, I wondered what nursery rhymes might be familiar to him – and this is when I discovered the ‘Three Craws’ (described as a Scots classic).

The ‘craws’ would be known in England as crows. In Scots it is a fine onomatopoeic rendition of the cry which the birds make. The craws in the rhyme are not doing very well. The first craw is crying for its mother; the second has broken its beak; the third is unable to fly. With the kind of simple repetition that makes the most effective nursery songs, each verse describes the crows sitting on a wall, sharing their woes on a cold and frosty morning. (It should be noted that the content of these verses varies, and people add their own).

At the end of one of the versions of the Three Craws, there is reference to a fourth craw – The fourth craw wasnae there at a’. It is an intriguing way to end. The rhyme is known as the Three Craws. The final craw never makes an appearance. Does this craw even exist – is it part of the gang? The song has a fourth craw, and yet it doesn’t. This bird is lacking, and seems to be the culmination of the losses that precede it. The craw missing its mother; the craw whose health has been impaired by a broken beak; and the craw unable to fly. It is an odd conclusion for our attention to be drawn to what is wholly absent.

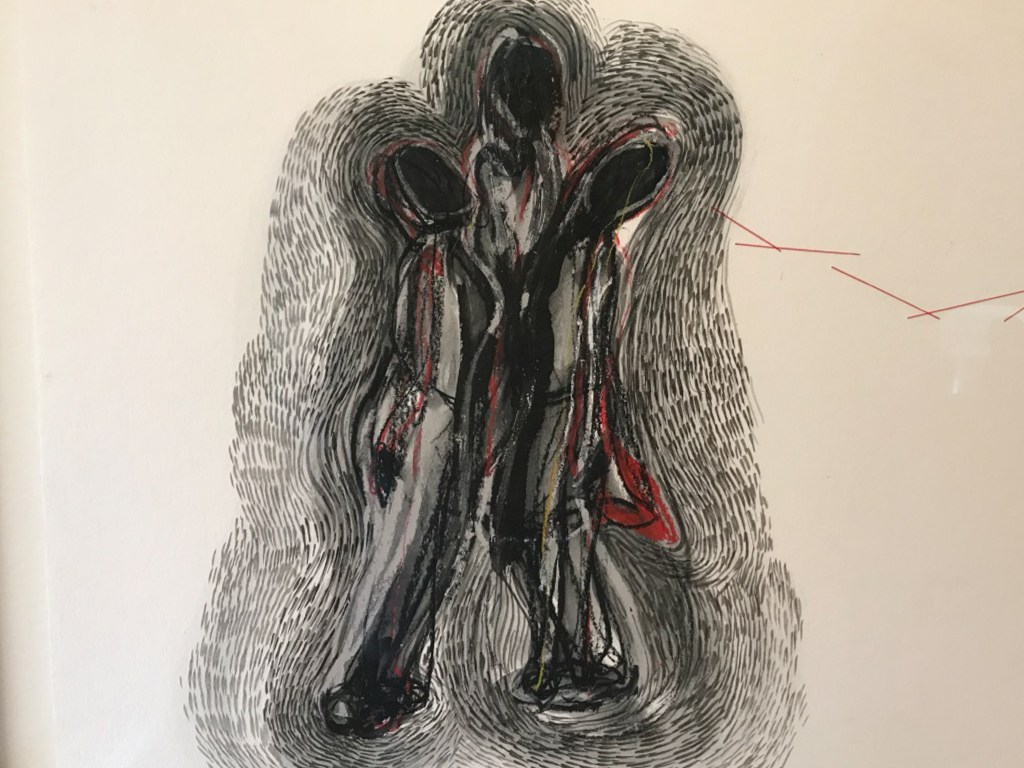

A poetic response to this missing figure has been created by the Glasgow-based academic and writer Nalina Paul. The work is entitled The Fourth Craw and perhaps reflects the power of narratives as they emerge from the darkness of absence – the sparks of our imagination kindled by our earliest encounters with song and story:

Too much is said about night –

its fullness jug-heavy with distance

poured out into star-mapped flight.But in the sky, protecting her addled head,

was a strange sense of grounding –

as if light were solid, for standing.And from these things –

sparks in the high darkness

a smouldering moon –

came music, the raven’s song.Its sound could wither the feathers of eagles

make fire from ice

play tricks with existence

changing form at a whim.In the dim-lit great hall of glittering stories

Nalini Paul ‘The Fourth Craw’ 2015

the broken shine of the moon crackles.

The fourth craw is an absence and also an invitation. Travelling through Glencoe a couple of weeks ago I was reminded how much the landscape of Scotland fires the imagination, and has inspired many different forms of art. The colours and textures of the mountains; burns that gush with great force after the regular downpours; and trees lousy with lichen, branches encrusted in moss. Glencoe can hold a magical, childlike, atmosphere – even before it is layered with human narratives of heroism and betrayal. Sadly, as walkers and climbers discover every year, it can also be a very dangerous place.

The Three Craws suggests that, when we lament or suffer injury, being in company can make a difference. The birds are a small community of sorrow, who end by sharing an experience of the fourth bird’s absence. Even at a young age it appears that we prepare people for one of the central experiences of life, as well as providing the space for wonder, and the work of our imagination.