In the weird and wonderful world of Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift described servants who performed a particular occupation encountered by Gulliver on his third journey. These servants were called ‘flappers’ and their job was to accompany their master or mistress and make sure they were paying attention to what was going on. They did this with the aid of an inflated bladder on a short stick which, when they deemed it important for the person to be alert and listening, was used to flap them on the ear with the bladder. Equally, if it was something they needed to look at carefully, to flap their employer – gently – upon the eyes, thereby preventing them falling down a cliff.

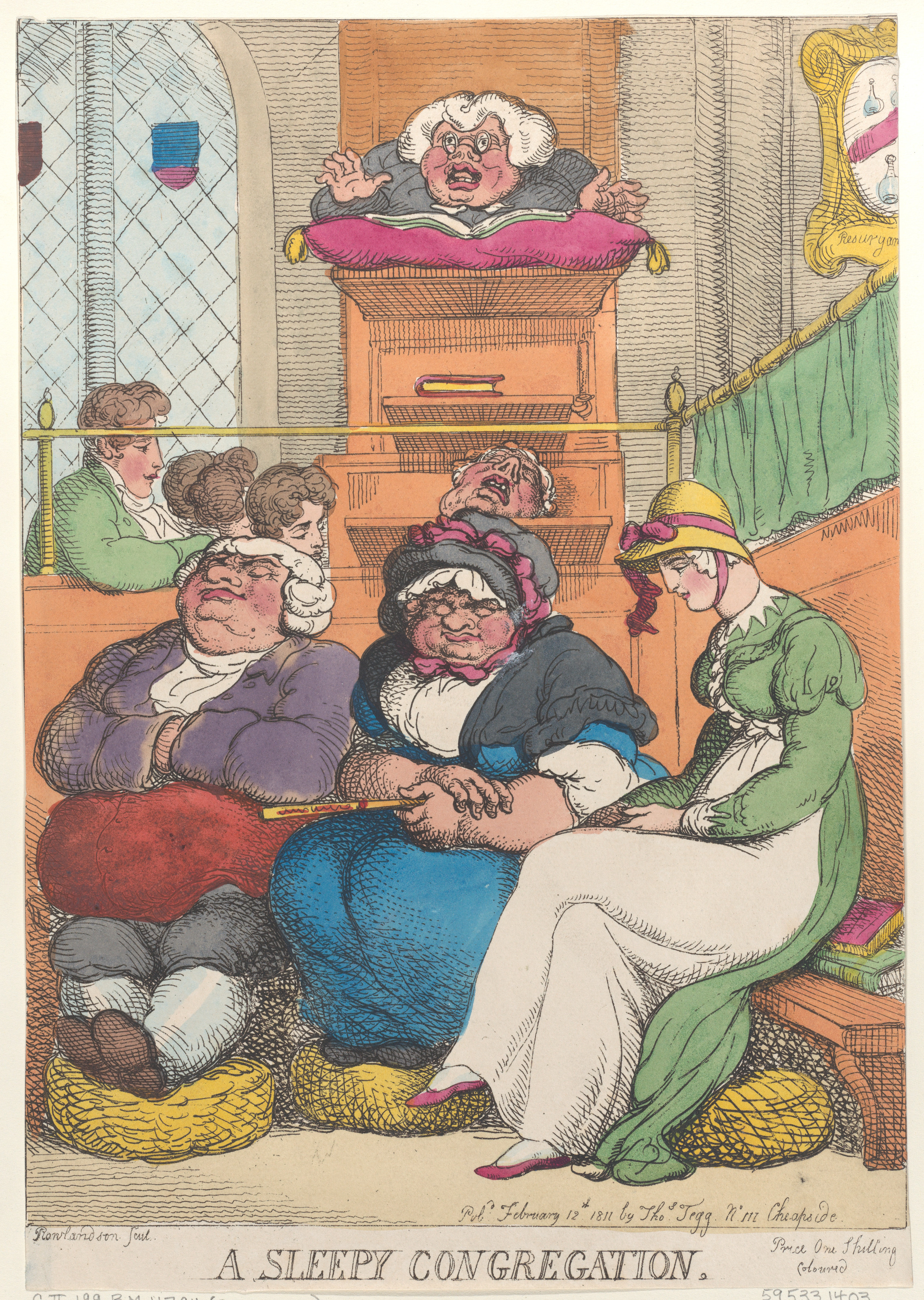

This rather dramatic premonition of contemporary mindfulness was Swift’s satire on the distractedness and self-absorption of philosophers. These 18th century thinkers are portrayed by Swift as disconnected from the world around them, requiring a ‘flap’ or, I would suggest, a slap, to reawaken them to reality. Gulliver was unimpressed by the aristocratic figures who needed flapping, and spent more time conversing with the flappers themselves who, of course, had to pay attention to the world on behalf of others. Swift would be aware that his description is reminiscent of the role played by court jesters, who also used inflated bladders, and were sometimes the only people who could speak truth to power.

It is not easy to see the world with clarity. Often our gaze is overlaid with memories and interpretations that make our observations conform to views we hold already. This can mean that we fail to discern new patterns or new dangers, in a context where we pull reality towards the norms of our own expectation. I have written before about the value of stringent seeing and speaking, when we try to strip away the layers we impose and see something afresh. It is not easy. Perhaps we all need a flap to the head now and then.

Until I began preparing a sermon for Palm Sunday I hadn’t noticed a comment toward the end of the appointed Gospel reading. St Mark tells us that on entering the Temple, Jesus remained there until ‘he had looked around at everything’. Not preaching; not teaching; not healing or anything else: simply looking. Further research led me to discover that the Greek word used here, περιβλεψάμενος, occurs only seven times in the gospels with all but one of these found in Mark. Why is the evangelist so keen to make this point about the behaviour of Jesus?

Referring to an earlier use of this word in Marks’ Gospel, one suggestion is that the pause for observation “helps to intensify what Jesus is about to do” (Christal, J. 2011). This could be interpreted as a word used to convey dramatic effect: something major is about to happen. That would fit with Jesus’ Palm Sunday entry into Jerusalem and the impending denouement of his mission. Equally, it is possible that Mark’s presentation of the passion captures a growing disparity between what Jesus was realising about the coming days, and a world unaware of events that would come to change history. It reminds me a little of the 2011 film Margin Call about the 2007-8 financial crash. A young financier, working for a large company, had calculated that the world was on the eve of a commercial meltdown. As he is driven across the city he gazes out on a world he knows is about to change, where everyone he sees is oblivious to how their lives will be altered. The character ‘looked around at everything’ because nothing would ever be quite the same again.

I am not convinced that having a flapper around to bop my eyes or ears would necessarily help me to see the world any more clearly. Like the ping of a message on my mobile phone, it would probably lead to irritation. Nevertheless, the point Swift is making is entirely valid. We are parochial and complacent creatures, wrapped up in our own concerns and often lacking the will to shake up our way of seeing the world. In a church where there is often an emphasis to ‘make disciples’ and to be incurious about a theology that questions our way of looking, it might help to remember that Jesus took the time to simply pay attention to the world. At the start of Holy Week it is a helpful reminder to us to ‘look around at everything’. To allow the narratives of Maundy Thursday and Good Friday to jolt our compassion into life, and to look forward with hope to the day of resurrection.