On holiday I am enjoying the time to read three very different books. One is poetry; another a novel; and the third theology. Despite being different, I am also seeing (or making) many connections between the narratives. This is unsurprising in one sense as I am their common denominator: the one reading. Like the handmade and unique marbled pages in each of the first edition volumes of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, we perceive our own patterns as we mark and experience the stories mediated by print.

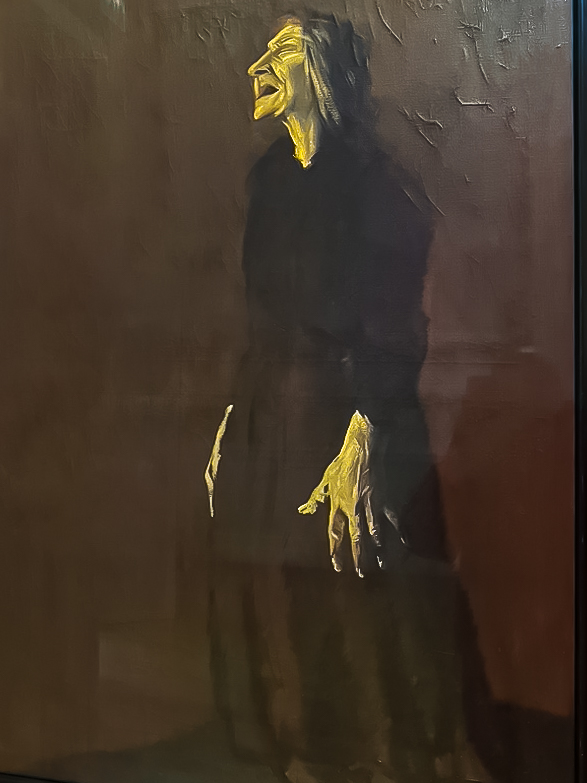

I came to A Dark and Stormy Night by Tom Stacey via an unusual route. At home we have a sculpture bequeathed by an old friend. In doing some research about the sculptor I came across the fact that her husband was a writer. In this novel, a bereaved suffragan bishop – a Dante scholar – gets lost in a forest in darkness while seeking a redundant chapel. It is notable that the bishop lived with and through his wife’s dementia – something Tom Stacey knew about at first hand. His description of this resonates strongly with what I experienced of my mother’s cognitive decline several years ago. Stacey’s insight evidently comes from deep and costly personal experience:

You are forever packing and re-packing to go home. To tell you we are at home only serves to rile you. This lost inner home of yours is never locatable.

Transgressing the boundaries of normal or accepted behaviour is a strong theme of Allan Boesak’s Children of the Waters of Meribah. Boesak is a South African theologian with an abiding commitment to liberation theology.

In a chapter exploring the story in Matthew’s Gospel of the Canaanite woman who comes to Jesus seeking healing for her daughter, Boesak conducts a masterclass in hermeneutics. Experience shapes both writing and reading. Unsurprisingly, Boesak is alert to the location of this account:

She is a Canaanite, the people whose land had been conquered and occupied by Jesus’s people.

What should have been home was no longer home or, at least, a place now made strange and punitive. The experience of being South African leads Boesak, and the scholars he cites, to read this account with the painful insight of experience. The woman comes to Jesus in a “spirit of protest and reclamation”.

The final book is a collection of poetry by Koleka Putuma entitled Collective Amnesia. It is a work that has set records in South Africa in terms of poetry sales. Inevitably, with a heritage of the Group Areas Act, this is a nation that continues to live with “ongoing collective trauma” for countless reasons, not least the dispossession of peoples’ homes. Putuma writes out of her experience with skill, candour and wit.

You will realise that the elders in the room

Learned the alphabet of hurting and falling apart differently

For you, healing looks like talking and transparency

For them, it is silence and burying

And both are probably valid

And

Then

You will realise

That

Coming home

And

Going home

Do not mean the same thing

From the poem ‘Graduation’ in the book ‘Collective Amnesia’ by Koleca Putuma