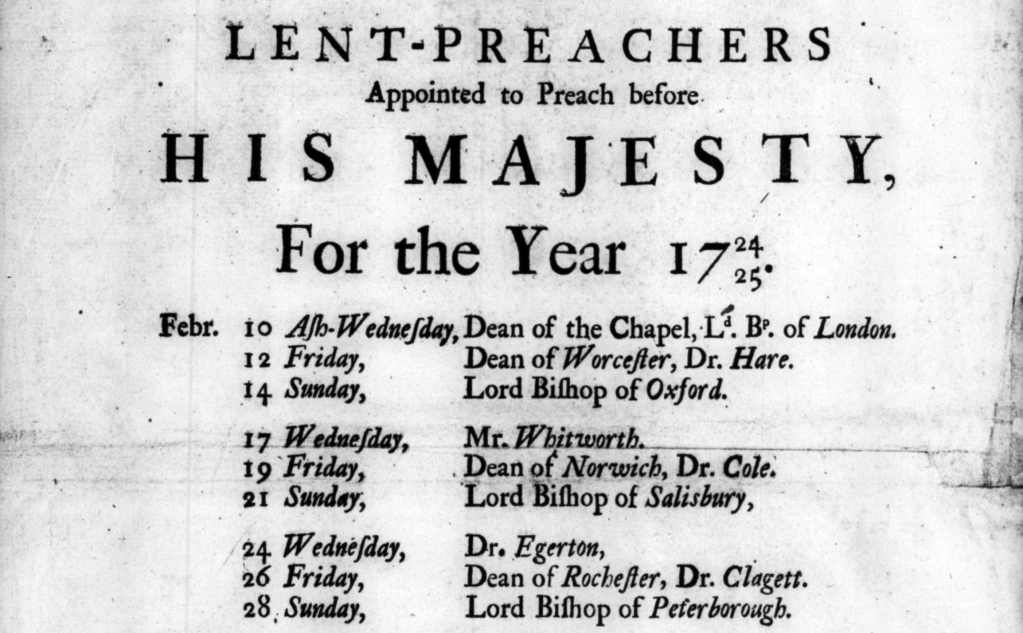

It appears as a small detail in some classical depictions of the Annunciation, but it is not uncommon to find a tiny baby Jesus surfing a beam of celestial light towards the Virgin Mary. We might take this to be no more than an artistic expression of the theological significance of what was unfolding at this critical moment at the start of the Gospel. However, there is more to this illustration than meets the eye.

A middle part of so called Mérode Triptych, created in 1430’s in the workshop of a Master of Flémalle, and kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Anyone familiar with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman will know that the clerical author, Laurence Sterne, makes play with the concept of “homunculi”. Developed to a significant extent by Aristotle, this idea centres on the belief that all the physical aspects of procreation resided with the man. Unbelievably small babies were thought to be present in semen which, at the moment of conception, were passed by the man to the woman. It is hard not to interpret this as a startling manifestation of misogyny. Life being so important it could only originate from a man; and pregnancy so inconvenient it must be the perpetual obligation of a woman. In Tristram Shandy this theory is mocked from the first page, when the conception of Tristram is interrupted by Mrs Shandy, who distracts her husband by asking: “Have you not forgot to wind up the clock?” The effect of this is to weaken the efforts of Mr Shandy, and results in irrevocable damage to the homunculus that is, and will become, Tristram.

It would be easy to underestimate the consequences of this belief. Sterne incorporates into his novel the real-life situation of the Duchess of Suffolk. When her husband and son died in quick succession she was granted administration of the estate. However, when it was contested, part of the appellant’s legal argument was the assertion that – based on an understanding of homunculi – she was not a blood relative of her son. The Duchess lost her right to inherit.

As the Church celebrates the Annunciation on 25th March it is worth asking the basic question: “What was going on?” The classical paintings of a tiny Jesus heading towards Mary imply that the infant saviour was a divine homunculus. The mother of Jesus was simply receiving a delivery from the Almighty, leaving her virgin state unaltered and confining her responsibilities to safe carriage. At its most extreme, Mary would be seen as having a vocation – but no blood relationship with Jesus.

In the classical world divergent views about conception include those of Aristotle, and an alternative approach can be found in the work of Galen. Galen’s understanding of conception sees both the man and the woman contributing seed to form an embryo. As Magdalena Łanuszka put it in a blog entitled “Flying Baby Jesus”, the homunculus interpretation lacks serious theological foundation:

Such a depiction suggests that Christ was incorporated as a human child somehow beyond Mary’s womb and then “placed” in it. That weird In Vitro is of course an idea absolutely theologically incorrect. Jesus’ body was formed entirely out of Mary’s body, not somewhere outside it.

In a timely inclusion, the current issue of The Church Times features a review of a new book focusing on the embodied experiences and theologies of birth. Pregnancy and Birth: Critical Theological Conceptions challenges the dearth of theological work done on these major topics. It is not difficult to imagine that if men underwent the experience of pregnancy, the number and variety of titles on these subjects would be immense. In another review of Karen O’Donnell and Claire Williams’ new book, Dr. Emma Percy, a researcher working in this field, offers some concluding reflections:

Pregnancy and all the complexities around reproduction should not be a niche topic, just for the feminist theologians or those who have been pregnant. We are all born from a body that gestated us for months. Jesus, as O’Donnell reminds us, shared this very human experience in the womb of Mary. There is much for all to learn from taking a more realistic look at a bodily experience that is so fundamental to our being human.

Emma Percy book review in Theology. First published online January 8, 2025

Sweet flying baby Jesus should concern us all. How we respond to this framing of the Annunciation and Incarnation is fundamental to our understanding of Christianity, and the God we worship. Sterne turned the evident nonsense of the homunculi into satire, but underneath the wit is a profound question about the humanity of the God in whom we place our faith. From what I have read, it is uncertain whether the writers of the Bible shared a uniform understanding of conception: they almost certainly didn’t. (There’s an excellent article about this by Laura Quick entitled Bitenosh’s Orgasm, Galen’s Two Seed and Conception Theory in the Hebrew Bible). Ultimately, when we lack the understanding of what the authors of Scripture thought when they were writing, we need to arrive at our own conclusions as to whether our interpretation enlarges our love of God and of neighbour, or diminishes it. For me, the idea of Jesus as a foetus implanted in Mary’s womb by the Holy Spirit undermines a primary doctrine of Christianity; namely, that the Word made flesh is both fully human and wholly divine.