Increasingly I find Radio 4 a disturbing listen. Not because the content is controversial (usually), or offensive, but because every time I switch it on I realise how much I don’t know. Whether it’s In Our Time, or some other consideration of a niche topic, I’m made aware of the vast range and depth of human knowledge about which I was oblivious. One example of this arose last week, listening to the Seven Deadly Psychologies. While I certainly have views about why greed is bad, this programme delved into the mechanics of why this might be the case. In the discussion there was a fascinating debate about the fact that, generally speaking (but with notable exceptions), research has demonstrated that rich people have less empathy and compassion than poorer people. In charity, the poor overwhelming give away a significantly higher proportion of their wealth when compared with the financially advantaged.

One reason offered to explain this was that wealth meant people became more distant from communities. It was not possessing a fortune per se which caused this lack of compassion, but the acquisition of space. The consequence of an exclusive lifestyle is that it removes us from close company of our ‘fellow-passengers to the grave’, to quote A Christmas Carol. In turn, this increasing remoteness appears to dull the understanding of the thoughts and feelings of other people. Richer people often feel entitled to their wealth – and perhaps see poverty as simply other people’s failure to accrue resources. Perhaps some of the present UK Government should listen to this episode.

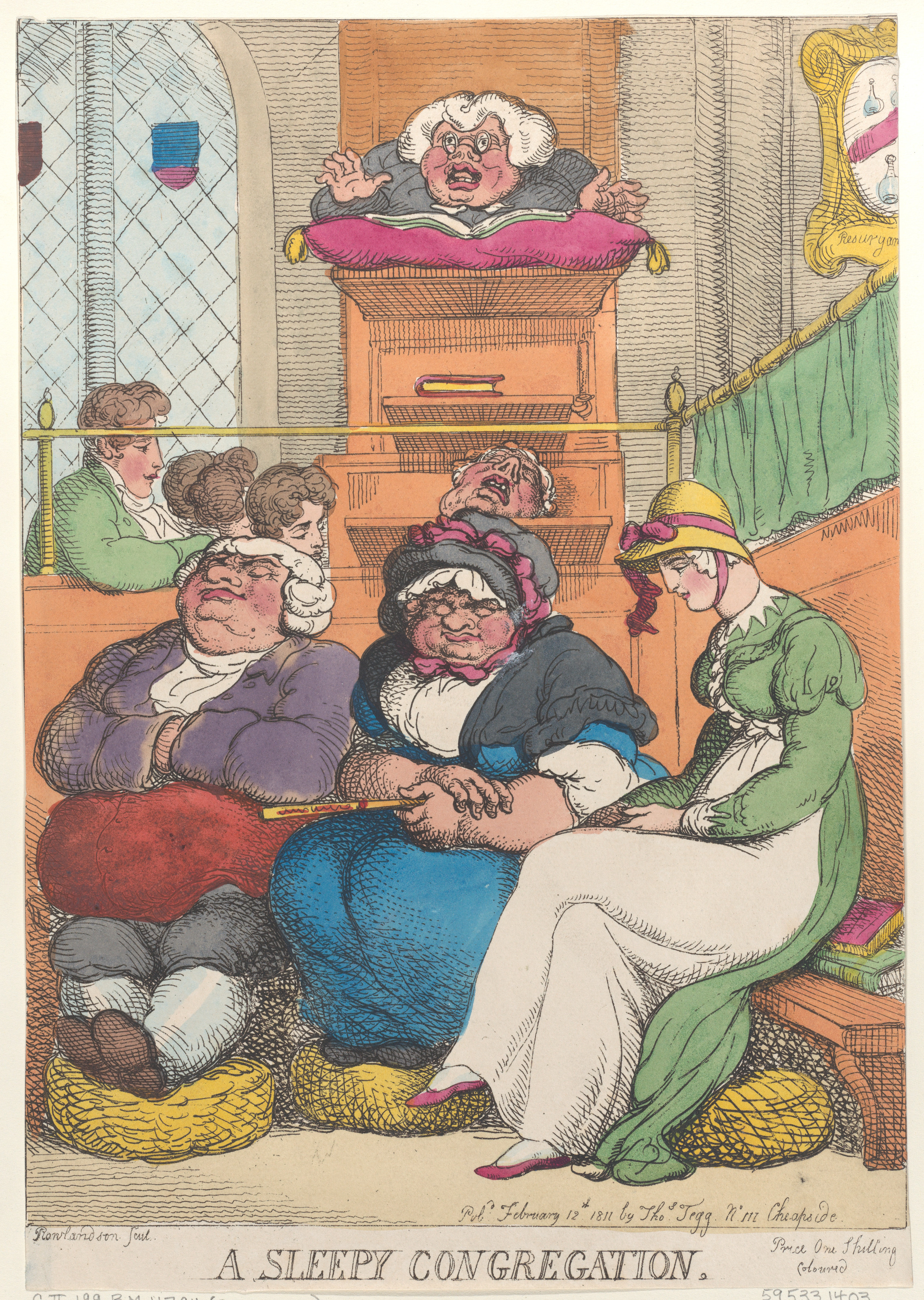

A crowded nativity scene in St. Hippolytus Pfarrkirche, Zell am See, Austria January 2023

While wealth and power no doubt brought King Herod a significant ‘exclusion zone’ this can hardly be said of Jesus. The narrative of the nativity describes a Bethlehem bursting at the seams. In the traditional portrayal, Jesus and his family are cheek by jowl with the beasts of the stall; receive a stream of uninvited visitors; and find themselves in a town where every bed is taken. Lack of worldly privilege ensured that Jesus grew up close to a wide variety of trades, in a community where modest livelihoods required people to cooperate.

Sovereignty in a cattle stall is one example of the paradox that runs through the Christian story. If wealth dulls our capacity to be compassionate it can also diminish our ability to recognise a God who expresses a preferential option for the poor. A God who, in Christ, is able to hear the plea of the Syro-Phoenician woman; the prisoner on the cross; the dilemma of the rich young man. Only when the Word-made-flesh pitches its tent in the heart of humanity is the gulf between God and creation closed. Ultimate power and splendour, commanding more space than we can ever imagine, chooses to renounce entitlement and make the ultimate identification with humanity.

For Dietrich Bonhoeffer the paradox lies partly in the idea that this God is not seen easily by those who have the most resources, or education, or stability in their lives.

“The celebration of Advent is possible only to those who are troubled in soul, who know themselves to be poor and imperfect, and who look forward to something greater to come.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Knowing our need for one another, and our need of God, is a prerequisite for our spiritual growth and maturity. It is one of the reasons why Advent is an uncomfortable season. Many of us recognise the greed we feel for our own space, and to have the freedom to do as we wish. Community implies compromise and association, experiences which appear to have fading appeal in the West. However, to know God seems to require us to be immersed in the dependencies of human society – a truth which both Advent and Christmas impress upon us each passing year.