Until Ash Wednesday I had never thought my ancestry was connected to slavery. My forebears were working class people, engaged in factory labour and domestic weaving. They acquired no wealth and owned no property. Like so many in Lancashire in the 19th century they were caught up in the Industrial Revolution, trying as best as they could to survive. However, their connection to slavery was to spin the cotton that was at the heart of the exploitation of people and the associated growth in international trade.

It may seem odd to think of this as a connection with slavery. The usual focus is on the wealthy institutions that owned slaves, controlled plantations or invested in the transatlantic trade. However, it was a business that involved almost everyone. From governments to the academy, the creation of public libraries and art galleries, the economic benefits gained from slavery are in the fabric of British society. While there is a range of opinion about the precise economic advantage that resulted from transatlantic slavery, it is estimated that the British working class benefited by a small but significant rise in their living standard:

The change in worker welfare is the population-weighted average of the change in the real wage in each location and equals 3.06 percent, implying substantial welfare gains for domestic free workers from the enslavement and exploitation of black Africans in colonial plantations.

Heblich, S., Redding, S. J., & Voth, H. J. (2022). Slavery and the british industrial revolution.

It is understandable that Ash Wednesday made me think of this connection. Isaiah tells us: “Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke?” Sadly, one of the most grievous sins of our age is the toleration of inequality and the yawning gulf that exists between rich and poor. At the end of a year living in Argentina, almost 40 years ago, I had a conversation with my Spanish teacher. During my time in South American I had witnessed the severe challenges facing many communities. In my early 20s, I undoubtedly had a more passionate idealism than I do today. I asked her how I could return to my life in the UK knowing about the huge disparities in wealth and power which I’d seen. The answer was: “you’ll get used to it; you’ll feel differently over time”. It was a wise and accurate prophecy. It might be the greatest sin to accept – even joyfully embrace – this kind of moral anesthesia. To remain untroubled by the way of the world or simply wring our hands at the daily TV news, saying: “if only there was something we could do!”

The scriptures for Lent speak about lament that leads to action. We are not required to exhibit our distress, or acts of justice, but we are required to feel the shocking truth of the reality that our world falls far short of the Kingdom of God. It is only when we see and understand the terrible reality of a world which is constructed by entrenched inequality that we can ever hope to find a different path. It is tempting to see ourselves as unconnected from the blasphemous operation of transatlantic slavery, but the economic advantage it delivered is rooted in the institutions of the West (not least the Church). Work is being done to respond to this truth, but it is yet to be seen how successful it will be in achieving any kind of restitution. We speak of both financial currency and the body’s blood being in “circulation”. Money earned through oppression and slavery may be produced in on particular place but, once it is in the financial system, it becomes impossible to point at one part of the economic body and say “it isn’t there”. How would we know with complete certainty?

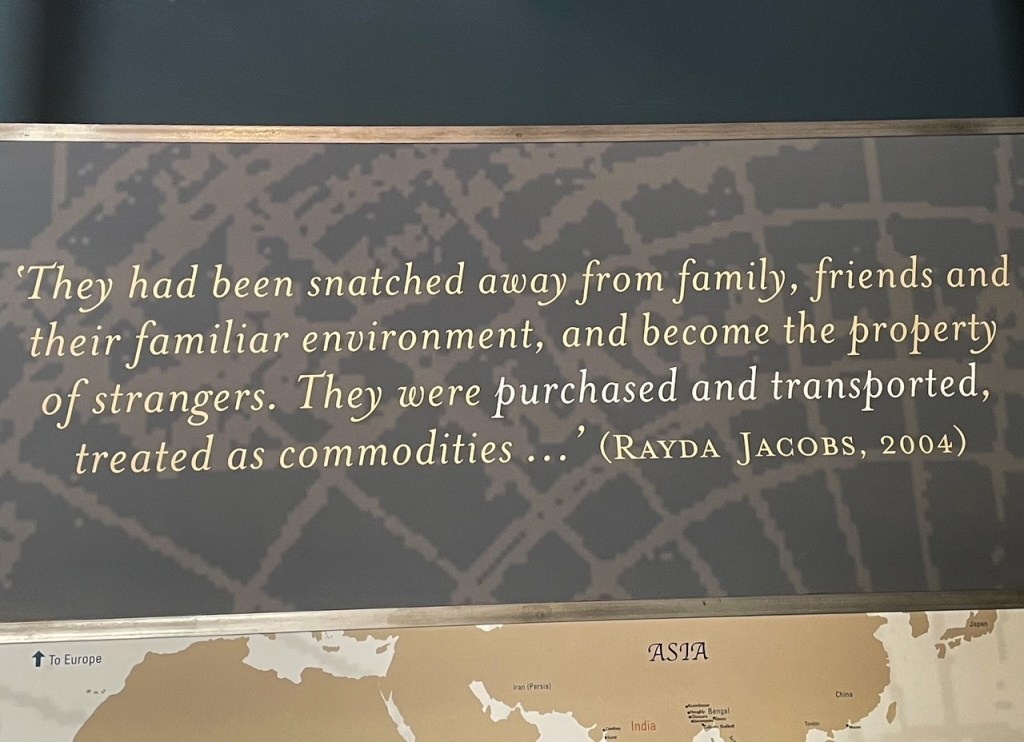

The bonds of injustice continue to shape our world. Visiting South Africa I am reminded once again of the legacies of slavery, not least in the system of apartheid. The abolition of laws is one thing, but the calling to be awake and alert for the ingrained divisions of an unequal world requires soul-work if we are to prevent the slide backwards into attitudes now surfacing in the USA and elsewhere. Restitution is more than reparations and requires a profound recognition of an evil which must be countered step by step, each and every day.

“Slavery cannot end through laws alone. We who survived were taught to hate ourselves, our bodies, our histories. I learned this in the way that I held my body as a thing despised, ashamed. Why do we need a museum of slavery? Surely the cobbles, the walls and the hills scream of that past. But outside all we hear is the forgetfulness of the city. Here, in this museum, we will call again into memory our languages, our resistances, the worlds we made in the city of slavery”

Quotation from Gebeba Baderoon, 2020, in the Museum of Slavery, Cape Town, South Africa