Interpreting complex and dynamic information is never easy. As a hospital chaplain I was familiar with the necessity to appraise a situation and make a decision under significant time constraints. Finding the right words, rituals or other aspects of pastoral care, when death is imminent, has the capacity to focus both heart and mind. On rare occasions, when the family and friends of someone nearing the end of life presented a wide range of beliefs, great care was needed to find a form of recognition and support which was of genuine service to all concerned. Getting it “wrong” can have enduring consequences for the bereaved.

Five years ago we were getting to grips with the new phenomenon of SARS-COVID-19. Hardly anyone in society had experienced a serious pandemic in the UK. Working in the care sector, it soon became apparent that many leaders lacked the heath care background which would have supported a speedy awareness of the consequences inherent in the unfolding events. Perhaps most significantly, the understandable desire for clear evidence and guidance prevented early actions to stem the rate of infection. As I commented at the time, in a pandemic, waiting until the evidence is utterly compelling is the definition of leaving it too late.

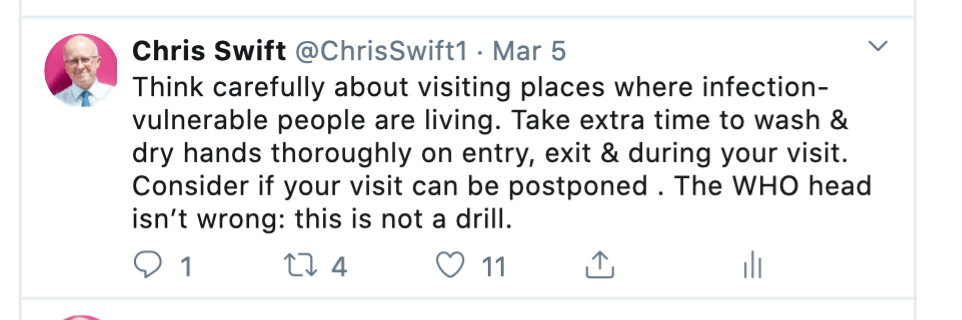

“we want to avoid any over-reaction but preparation seems wise”

Chris Swift email 11 February 2020

Viruses are most effective in the period when there is no immunity from prior infection; people feel no motivation to alter their routine behaviours; and when a delay between infection, illness and public reporting lasts several days. In care homes, where vulnerable people are kept close together, rooms are warm and many residents might forget requests to change behaviours, the risks of an easily transmissible respiratory infection are severe. By 5 March 2020 there was sufficient evidence available to determine that this wasn’t a rehearsal – but the emerging reality of a disease which spread quickly and had a high mortality rate amongst older populations. This was probably the prime date in the UK when decisive changes in behaviour would have saved the greatest number of lives. On 11 March 2020, I wrote to a colleague stating that, in my judgement, we were passing the outer marker of when it would be most beneficial to act. Finally, on 23 March, the UK went into its first national lockdown.

In 2020 different people came to a realisation of the need to act at different times. However, those differences undoubtedly had real-world consequences. If prompt actions made no impact there would, presumably, be no differences in the mortality rates of different countries. But there were significant disparities. Probably the best time to have acted in the UK would have been in the first few days of March. By the 11 March it felt as though we were heading into uncharted waters, beyond the zone in which wise actions would have made a significant difference to the incursion of infections. Sadly, in the UK and elsewhere, this delay undoubtedly multiplied the number of deaths; the incidence of care staff’s trauma; and the inevitable distress of relatives unable to be with loved ones at the end of life.

Five years still feels to be too brief a time for the world-changing events of 2020 to be fully digested or understood. It might be the case that we are in a phase of denial, finding it too difficult or too contentious to rake over the ashes of SARS-COVID-19. However, a time will come when we are ready to talk about the remarkable and tragic events which transformed our collective experiences of everyday living. Perhaps, when the UK Covid-19 Inquiry finally reports, we’ll be in a better place to take a measured view of what the global pandemic meant for us, and the lessons we can take into the future. Sadly, watching the world in the past five years, the international solidarity of lock downs and a shared experience of a sudden increase in mortality, appears to have done little to generate an enduring sense of our common humanity and interdependence. In times when threats to human life are intensifying and growing, the need to interpret dynamic data at a point when wise actions can still shape events, remains a critical need.