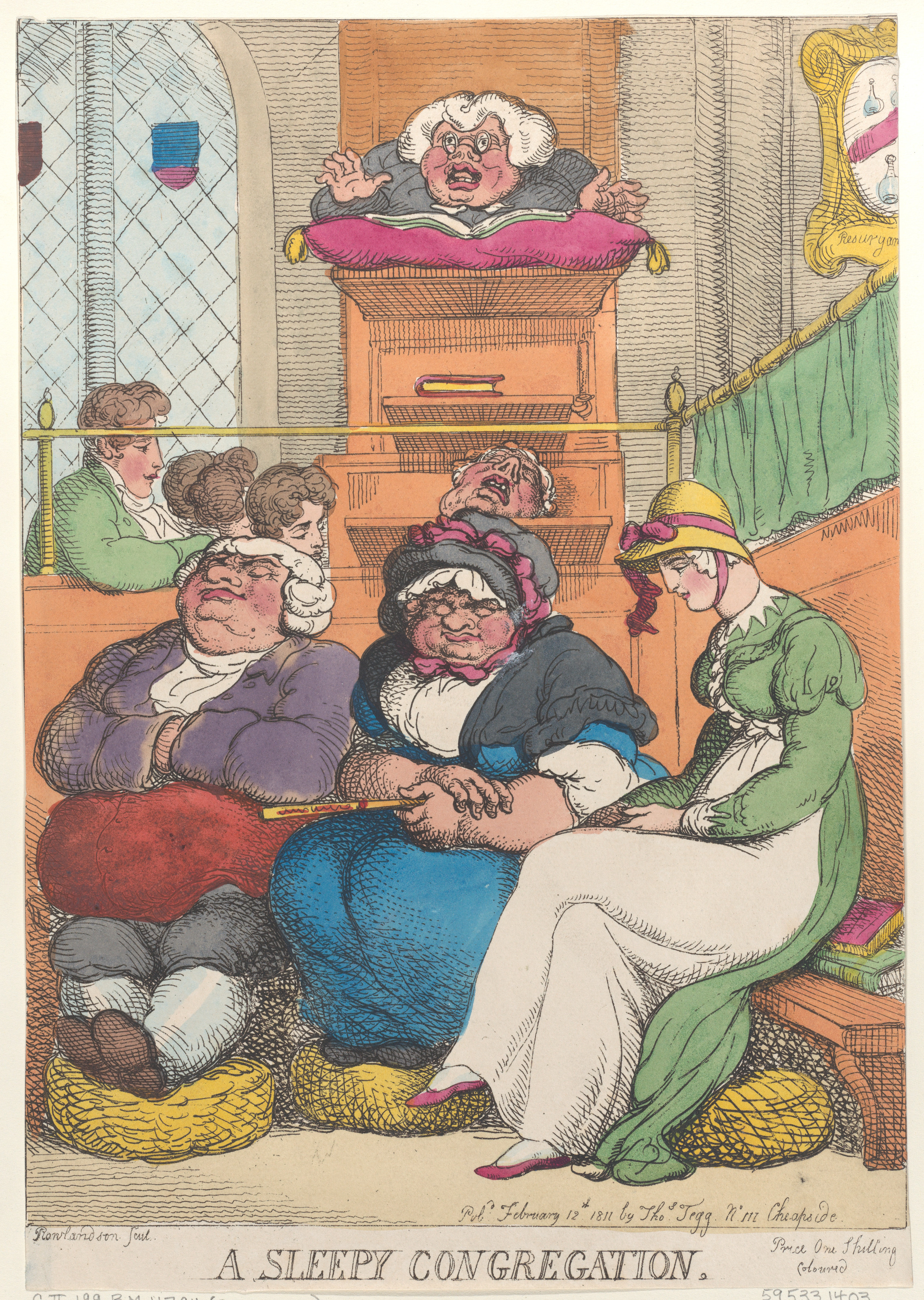

The statement that ‘the parish system began to break down’ sounds like a commentary on the C of E in the 21st century. In fact they are words written about the church in the 18th century, taken from an article concerning religion and satire, by Misty G Anderson. It is a salutary reminder that the Church of England has experienced several phases of breakdown since the reformations of the 16th century. Anderson identifies satire as one of the most effective ways in which a highly privileged institution could be critiqued in public. This is because satire never makes things explicit, but relies on the audience’s existing awareness of the gaps between official rhetoric and the reality of practice.

‘Praise undeserved, is satire in disguise’

William Lisle Bowles, Alexander Pope (1820). “A reply to an “Unsentimental sort of critic,”: the reviewer of “Spence’s Anecdotes” in the Quarterly review for October [i.e. July] 1820; otherwise to a certain critic and grocer, the family of the Bowleses!!”, p.15

Satire always treads a fine line in achieving its effect. William Hogarth was warned that one of his prints risked being seen as an attack on religion itself – rather than the excesses of people’s interpretation. The definition of satire is far from easy or clear. On the whole it describes an artistic form which is intended to portray human behaviour in a humorous light, in order to make a political point or amusingly imply that a purported behaviour or action is susceptible to other (less attractive or virtuous) interpretations. Hence satire has often engaged with religions and religious practices to query the motives involved or the disparity between piety and more dubious practices. Many years ago I scripted a weekly cartoon that ran for a couple of terms at the theological college I attended. It was one way in which the weight and seriousness of ordination training was presented in a playful and creative light. It was quite popular.

Sadly, the C of E now appears to be so peripheral to much of society that it is seldom the subject for satire. As Gore Vidal observed, satire only works if you know the thing being satirised. Possibly due to the influence of the excellent Ian Hislop, Private Eye continues to identify some of the absurdities and failings of contemporary religion – but I imagine that the amount of print given to this has shrunk in recent decades. Indeed, more recently it has felt that the institution is satirising itself. In the last few weeks a message appeared from the Church of England’s main ‘X’ account heralding the opportunity to order a ‘new Christmas Advent calendar’. For a church where so many leaders try to maintain the distinctiveness of the Advent season this was a startling home-goal. The serious themes of hope, peace, love and joy surely deserve their own space for reflection and action this coming Advent?

There is, of course, the risk that satire is misunderstood or taken to be factual. In the past this has led the Church of England to publish a clarification. However, at its best, satire teeters on the edge of credulity precisely in order to accomplish its task. We see something – or read something – and need to take a second look. Could that be true? In this way satire has prophetic qualities, pushing an argument or behaviour one stage further and, suggesting that what may now be humorous, could soon become a reality. Perhaps a Church of England that surrenders its presentation entirely to generic marketing would start conflating festivals and shape the church’s life to follow without critical or theological enquiry whatever sells?

A healthy church should encourage the satirists. It doesn’t help if people are too holy to be human or so caught up in self-importance that they fail to understand how marginal (or non-existent) the Church is to so many people in England. Satire is the humour which is perhaps more than any other, ‘of the moment’. It only works, if it works at all, because it touches on the conceits and follies of a particular time. For example, who can listen to the UK-Covid-19 Inquiry enquiry and not feel that people living and working in Number 10 must have known the vast gulf that existed between their public statements and what went on behind closed doors? Clearly some did. When executed well, satire may help steer the church and the world into more authentic territory – and make us smile and wince in equal measure.

‘You can’t make up anything any more. The world itself is a satire. All you are doing is recording it’

Art Buchvald

With love and thanks from Veronix xxx