Management is an integral part of all organisations. It existed long before it was much spoken about or, indeed, became a field of study and development in its own right. Modern general management was introduced into the NHS following the Griffiths Inquiry in the mid 1980s. It paved the way for streamlining NHS processes and enhancing accountability which – eventually – even incorporated chaplaincy within its structures. Since then, in many organisations, I have witnessed and experienced the power of good management to exclude waste and improve efficiency. However (and there was always going to be an ‘however’!), there is plenty of evidence that contemporary management and executive leadership is far from perfect. Perhaps the instantaneous and seemingly universal response to Mr Bates v. The Post Office arises to a significant extent from the resonance of this story with many people’s experiences of institutional behaviour.

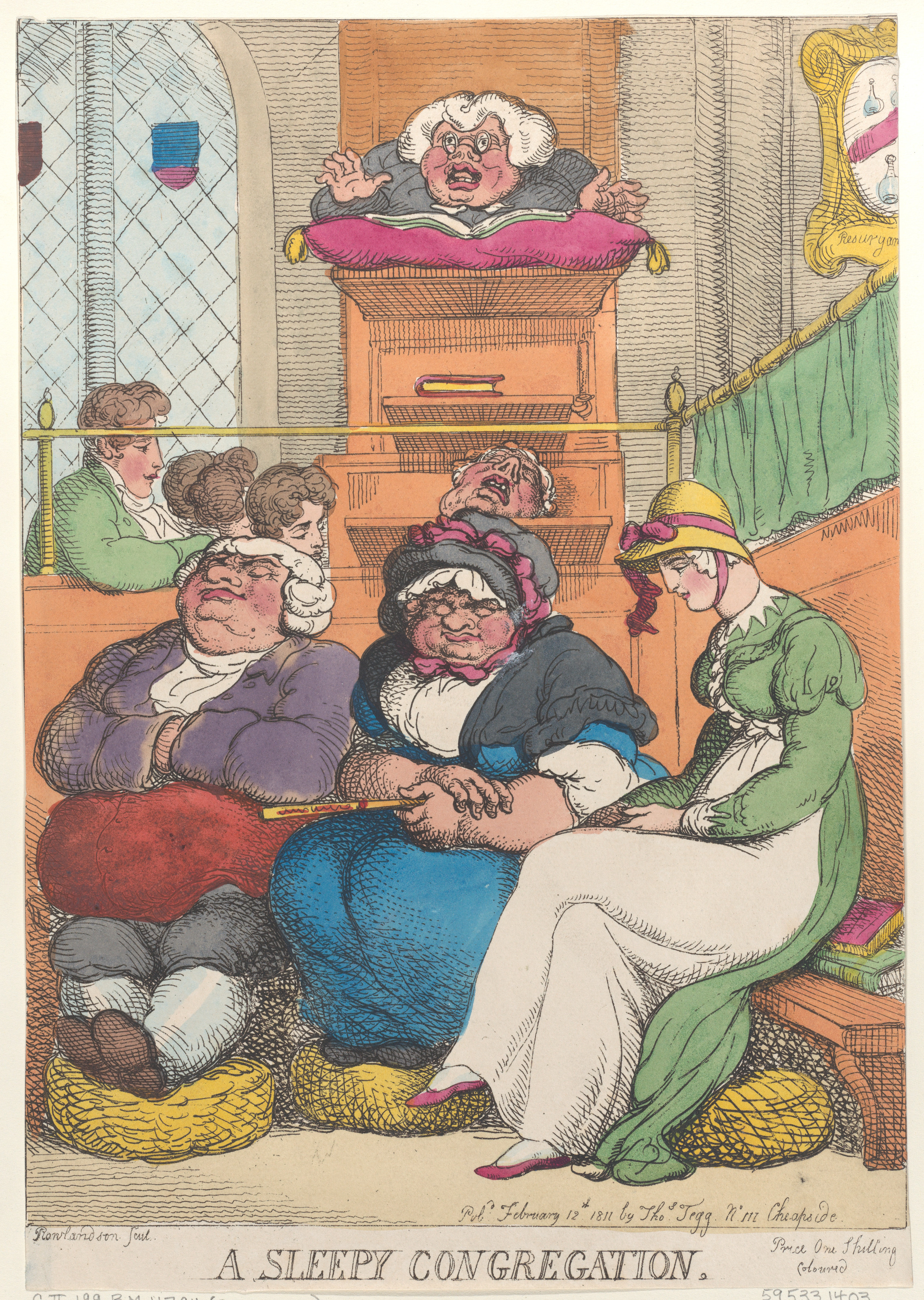

When I reflect upon my own professional journey there have been several key points when I have found myself in disagreement with a majority view. This is very inconvenient because, being naturally inclined to a quiet life, feeling compelled to express contrary views is time-consuming and energy-sapping. Often it requires detailed work to elucidate arguments and marshal the evidence that suggests – at the very least – that there is more than one way of looking at something. ‘Group-think’, especially when the leader’s views are clear and unequivocal, is far too easily generated in an environment which is unwelcoming of dissent. Over the years this is something I’ve observed in many contexts, including those of a research ethics committee and in church settings. The latter may be especially susceptible when the charisma of a Bishop is invested in a particular approach. Criticism of the approach can all too easily be perceived as criticism of the person.

It seems to me that a primary flaw in the case of the Post Office, and in many other institutions, is an inability to require a perspective 180° away from the one holding sway. For example, when a surprising number of post office staff were accused of fraud, and many maintained their complete innocence and were supported by local communities, why didn’t someone at a senior level think the unthinkable: what if they were right and Horizon was wrong? It isn’t difficult to speculate why a supplier might be reticent about admitting faults with a service it had provided. System error can be very costly and damage reputations (leading to even more adverse financial impact).

It would appear that often, as in the case of the Post Office, even independent reviews can encounter opposition if their findings differ from the dominant narrative of the organisation. When in leadership in health care chaplaincy I called on numerous occasions for an independent review of the operation of the Hospital Chaplaincies Council (HCC). There were many reasons for this, not least indications that something was wrong in the core operation of this Church of England quango. Eventually a review took place under Dame Janet Trotter, which concluded that the HCC was “too large and cumbersome for its purposes” and should be dissolved. Its findings were not welcomed by everyone and consequently the report was criticised from several quarters. However, the Hospital Chaplaincies Council no longer exists.

In leadership there is always more you could know, and the data will only ever be partial. Having a healthy appreciation of the gaps – the dark matter – is a key component in grasping the gravity of a situation. Being alert to seemingly insignificant anomalies can lead to the early detection of systemic failures. Simply closing ranks and moving into denial will only work for so long. Eventually, as the case of the Post Office demonstrates, you come up against the tenacity and determination that bends back into shape the distorted reality that huge resources have attempted to impose.

A wise leader doesn’t only want to hear the view of the majority. In 1 Kings chapter 22 we learn how King Jehoshaphat wasn’t content with the homogeneous advice of 400 prophets: ‘Is there no other prophet of the Lord here of whom we may inquire?’ Micaiah had the wisdom to make himself scarce when he knew the King wanted to hear from all the prophets. Micaiah was’t going to fall in line with the rest, and this would eventually earn him a slap and see him thrown into prison. Micaiah had the same inconvenient trait demonstrated by Mr Bates – he wouldn’t sign off on something he knew to be wrong.

“But Micaiah said. ‘As the Lord lives, whatever the Lord says to me, that I will speak.'”

I Kings 22:14 NRSV