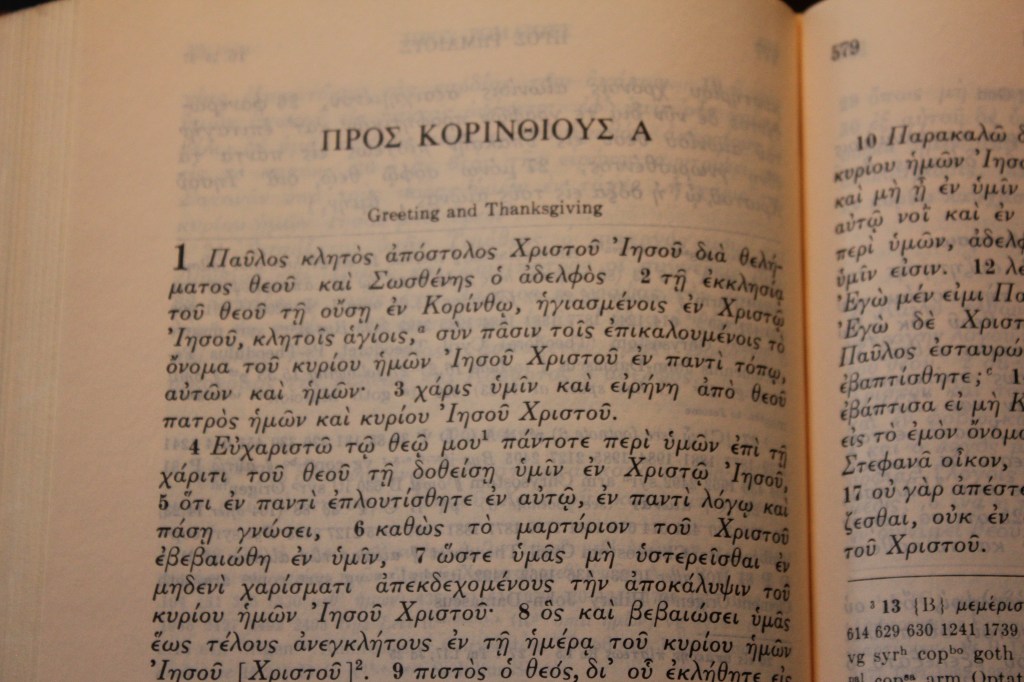

Images of God are scattered across the books of the Bible. We are familiar with many of these but occasionally one will snag our attention and lead us to pause and reflect. Recently I was reading Psalm 39 and was reminded of one of the less common metaphors of divinity:

You chastise mortals in punishment for sin, consuming like a moth what is dear to them; surely everyone is a mere breath.

Psalm 39 v. 11 NRSV

I am not a linguist and my grasp of grammar isn’t strong. As I began to think about the moth-God I came across a helpful article by DesCamp and Sweetser. Here, the debate about metaphor and simile for the Divine is set out with the insights of both theology and cognitive linguistics. It is worth a read. The metaphors we use to express our experience of God are critical to the way we think about God. Understandably, the words we use to indicate God assign different aspects of character, relationship and purpose. Altering the metaphors we use can be a revolutionary act: “new metaphors mean changing our licensing stories and deep cultural roots”.

Much of the time images for God can be overwhelming, expansive and vast. Alpha and omega, creator and judge. The more we understand about the stars and the universe, the more immense and bewildering the idea of God can become. At best, images point to this enormity. Yet the cause of vastness is also our creator, and during our evolution human beings formed words to describe our bespoke reality. Words that encapsulated a sense of the sacred:

who alone stretched out the heavens and trampled the wave of the Sea; who made the Bear and Orion, the Pleiades and the chambers of the south, who does great things beyond our understanding, and marvellous things without number.

Job 9: 10-12

Alongside these images of power and creative purpose are metaphors which suggest a different story. While the span of God’s activity is boundless, there is also hiddenness and intimacy. Alpha and Omega is like a moth – hidden in darkness, tiny and unravelling the threads of our vanity.

When I worked in the NHS I was often either involved in the training of nurses or engaged in conversation with them on wards. A comment that occurred a number of times was that for them, asking patients about religious matters was more difficult and embarrassing than asking about people’s sex lives. For a long time chaplains have spoken about this with a tone of impatience, implying that nurses simply need to get on with discussions about religion and belief. However, over the years I have begun to wonder more and more whether the instincts of nurses are right. That something as intimate as a moth needs handling with the greatest care; else clumsy enquiry causes nothing but damage.

DesCamp and Sweetser suggest that “metaphors actually constitute our relationship with God in crucial ways”. As God cannot be fully known, metaphors offer a creative and dynamic exploration of the qualities people experience in their spirituality. While God may not change, our experiences alters the metaphors we use to express a deepening relationship with the sacred. As I found, even images that are centuries old can still have the capacity to stir reflections that further our journey of encounter and understanding.