Wharram Percy is perhaps England’s most celebrated deserted village. What had been a thriving community set in the rolling and rich landscape of the Yorkshire wolds, expired from a range of causes. There is probably no clear identification of a seminal bow, but a host of factors eventually led to the eviction of the last two families, Even if the Black Death had not impacted on the village directly, it led to a host of vacancies in city trades and no doubt acted as a magnet for younger workers who sensed that the tide was turning on rural life. Famously, in The Deserted Village, Oliver Goldsmith depicts a bucolic haven that gradually gives way to the corrosive influence of commerce and the appetite for wealth. Goldsmith’s observations omit the pressures and constraints of rural living, but the gist of the changes he describes have left echoes across England. It is estimated that 3,000 villages became deserted during the Middle Ages.

‘Here as I take my solitary rounds,

The Deserted Village, Oliver Goldsmith, 1770

Amidst thy tangled walks, and ruined grounds,

And, many a year elapsed, returned to view

Where once the cottage stood, the Hawthorne grew,

Remembrance wakes with all her busy train,

Swells at my breast, and turns the past to pain’.

A generation earlier a similar theme was explored by Thomas Gray in his famous Elegy. The subject here is not a deserted village but rather the individuals who lived and died in an English village. Like Goldsmith’s later work, the virtues of a simple life are extolled and contrasted with the vanity and pomp of new wealth. It marks the emergence of a theme which lasted for the following two centuries – and includes the work of the Romantic poets. It was becoming clear that a way of life was ending in England and there were plenty of people who lamented its loss. It must be said that, on the whole, these writers were not the ones living without the convenience of a growing range of emerging technologies or, if they did, it was through choice. Even today, wi-fi access is an issue where rural communities often have to wait long after towns for the delivery of services most people take for granted. This was true for everything from measures to improve public health to electricity and the telephone. On a personal note, it was my parent’s generation which was the last in our family to have a living connection to people still working the land. In the 18th century most urban dwellers would have had links to relatives living and working in a rural context. They would have heard at first hand how life was changing.

In more recent literature, such as Remains of Elmet by Ted Hughes, the focus is not on deserted towns or distant generations, but on the supplanting of one people by another. Hughes observes changes that saw one set of trades giving ground to new occupations – or no occupation. He writes reflectively on life in the Calder Valley as industries declined and nature reclaimed the land while sealing the scars of human labour. In poems such as Crown Point Pensioners Hughes commemorates the ‘survivors’ who reached advanced age despite the legacy of war and the demise of traditional industries. Published in 1979 the collection of poems could not have been more timely: it was the year when Thatcherism began to eviscerate much of the North with devastating effect. Today, nature has indeed reclaimed many places once reduced to rubble, but the damage wrought by political change in towns and villages has passed down the generations. As Dr Jane Roberts observes in a paper published in 2009, drawing on her experiences as a GP working in Easington, government policies have frequently had the effect of disadvantaging people in communities where structural violence has had the greatest consequence. Narratives of individual improvement only add to the sense of failure for those whose life-opportunities have been dismantled and removed.

‘As long as we fail to acknowledge and confront the realities of patients whose illnesses and distress are often the manifest expression of the structural violence which encapsulates their lives we collude with the system and deny patients their basic human right to health and equal access to healthcare resources’.

Roberts, J. H. (2009). Structural violence and emotional health: a message from Easington, a former mining community in northern England. Anthropology & Medicine, 16(1), 37-48.

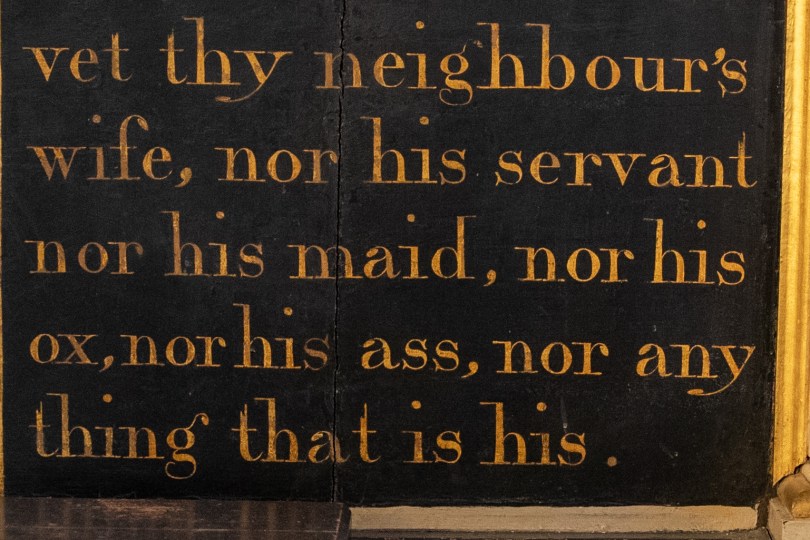

The last two families in Wharram Percy were evicted sometime around 1500 (to make way for sheep). It is hard to imagine what it must have felt like to abandon the village and make a fresh start elsewhere. There will always be change in the economic and social life of communities, but there is no doubt that some forms of change are better supported than others. When we understand that structural violence is a choice, rather than an inevitability, we create space for society to act in ways that promote a more inclusive social justice. In England, in the 2020s, we may all be forced to learn what the victims of capitalism around the world have known for centuries. Our economic way of life accelerates the acquisition of resources by the rich as it simultaneously increases the relative (and absolute) poverty of the people who generate that wealth. The question as to whether our economic system can continue to widen this gap will become more urgent this winter with steep rises in energy costs. To paraphrase Goldsmith, the deserted villages are a graphic example of the dramatic change ‘Where wealth accumulates’ and people rot.