I have long been a fan of The West Wing, Aaron Sorkin’s masterful creation of an imagined, plausible, and ethical US Presidency. Although the programme foretold the election of a president who was Latino, it did not predict the right wing backlash that would follow. A much weaker version of Donald Trump features in an episode concerning a Republican challenger to President Jed Bartlett, who the sitting Democrat sees off without difficulty. Alas, recent months have seen a catastrophic implosion of the Democratic opposition in the USA, with global consequences.

In one episode of the series Jed Bartlett is asked a question about why Airforce One’s take-off had been delayed. Before giving the prosaic reason, Bartlett eulogises for a moment about what a lengthy night flight can mean:

“A long flight across the night. You know why late flights are good? Because we cease to be earthbound and burdened with practicality.”

I write this onboard a BA flight which is about to leave Cape Town on Friday 21 March. We weren’t sure whether this flight would make it into the air, given events at Heathrow. Perhaps we won’t land in the UK – the equivalent flight yesterday ended up at Barcelona. Nevertheless, we will have a long night flight in all events, and perhaps Bartlett was right that there is something unusual and potentially uplifting and thought-provoking about traversing the planet in this way (albeit with environmental considerations and impacts).

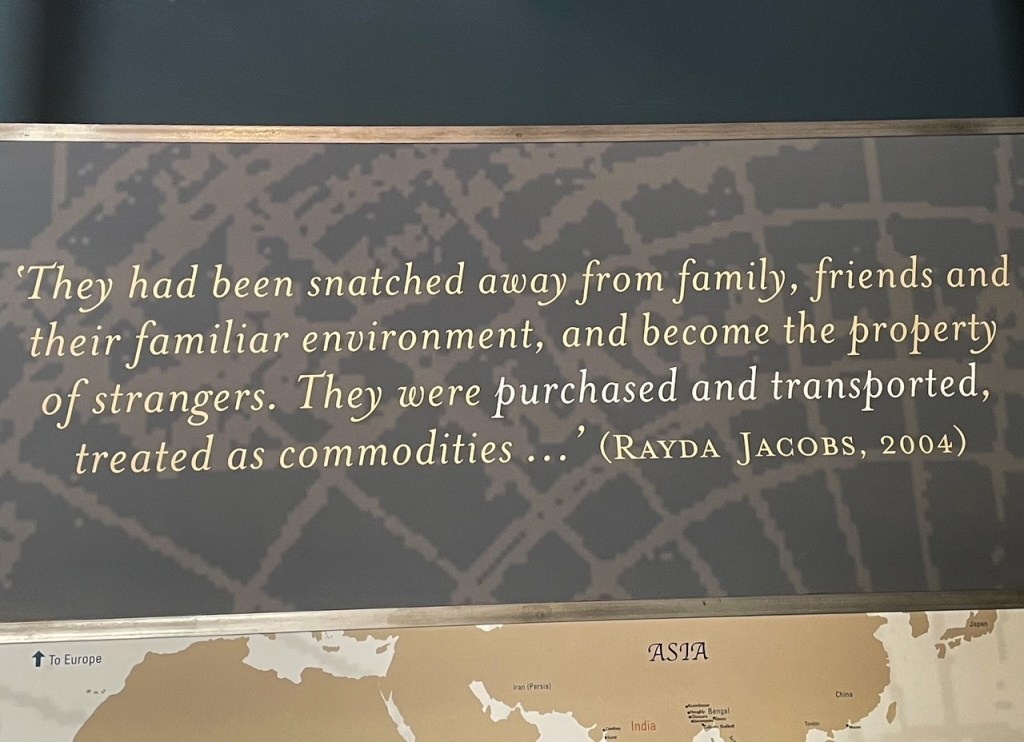

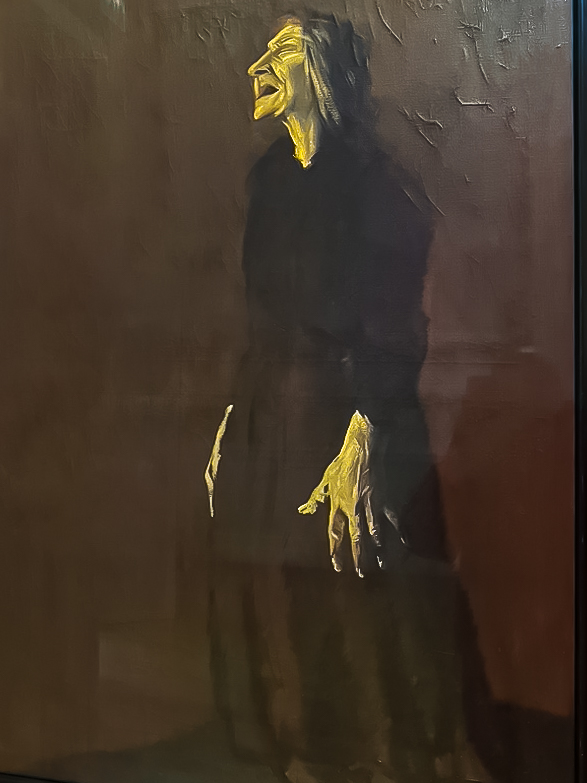

Once again South Africa has been impressive; challenging, and full of natural wonders. From visiting communities that experienced devastating flooding, to the wealthy areas of coastal communities along the Garden Route, we have once again experienced a country of contrasts. A nation where the enduring imprint of colonialism runs wide and deep. During our time there the SA Ambassador was asked to leave the USA and 70,000 Afrikaans have expressed interest in accepting refugee status in America. Making a nation is hard work – especially one so burdened by an evil regime that nurtured division as a basic strategy of education and government.

Perhaps due to the short span of our lives human beings do far too much far too quickly. Nothing appears to have been learned from COVID, recent global conflicts or the history that underpins Western privilege. In South Africa two experiences reminded me of our self-absorption and navel-gazing. One was the opportunity to see and photograph the Large Magellanic Cloud, a ‘nearby’ galaxy containing 30 billion stars, and only visible from the Southern Hemisphere.

The other, quite different experience, was to go underground and visit the Cango caves. Here stalactites and stalagmites have formed over tens of thousands of years, in some cases forming vast columns when growth up has met with expansion down. Extraordinary beauty created by incredibly slow drips of calcium infused rainwater. A process now slowed by global warming.

What is above us and below us is a reminder that the environment we value has come into being through both unbelievably big cosmic events and incredibly small and sustained changes that over vast stretches of time have a mighty impact. We do not tread lightly upon the earth, expending in a couple of centuries resources that have taken millennia to create. The relentless energy of the systems that we have built do not work in favour of the whole of humanity, or even the few that appear to reap the benefits of extracted resources. We are not living sustainably and the blind optimism of some that we shall always find solutions to the problems we’ve created may, in the end be shown for what it is: a convenient narrative to permit the continuing exploitation of our planet.