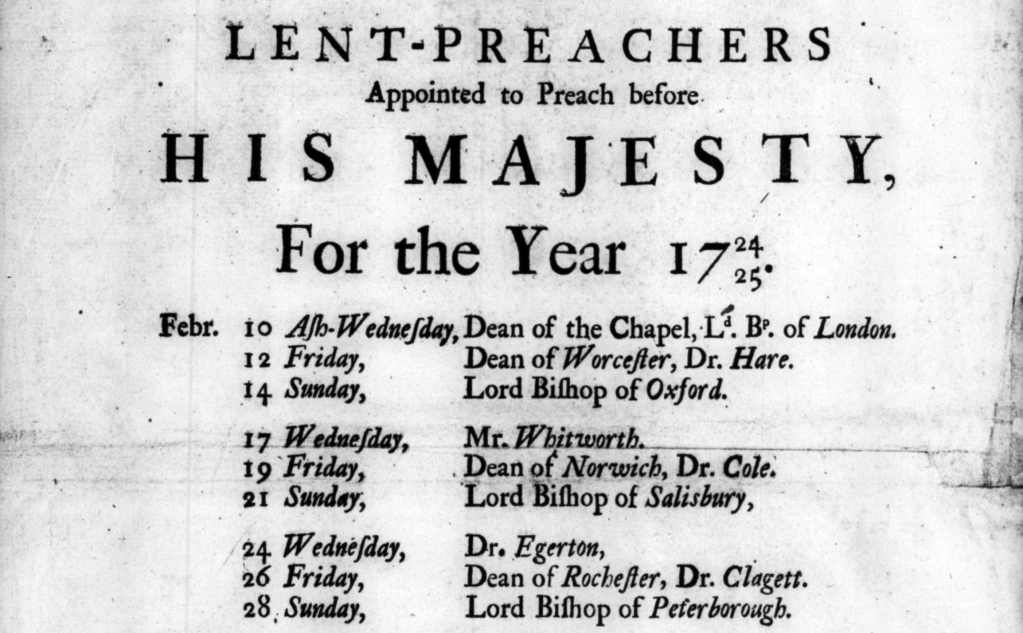

I usually skip through the online edition of The Church Times over breakfast on a Friday. It is a newspaper with a venerable history, having first hit the presses in 1863 (between the publication of The Origin of Species and the first sales of Turkish delight). In 1981 a scurrilous and highly enjoyable spoof of The Church Times was published under the title Not The Church Times, reflecting the popular use of the ‘not’ brand of satire in the 1980s. It came complete with adverts for high office, one of which stated:

Applicants are invited to apply, stating their public school, Oxbridge college, year at Westcott House, and Lodge.

Sadly, I would qualify on only one of these criteria and even then, by 1990, Westcott was no longer the powerhouse of episcopal chumocracy for which it was once renowned. This undoubtedly explains why, when there is presently a surfeit of episcopal vacancies in the Church of England, no mitre is likely to fall on that pate so propitiously cleared of hair, which would be enhanced immeasurably by the imposition of a pointy hat. Alas, as Cervantes put it in Don Quixote – quoted later by Sterne – with a head so beaten about by the vagaries of life, if mitres were “suffered to rain down from heaven as thick as hail, not one of them would fit it.”

In recent years the criteria for preferment have undoubtedly changed from those in the 1980s. Favour has fallen on evangelical candidates; those perceived to have been successful in an organisation other than the church; and, more than anything else, priests who have a story of leading church growth. Once again, my credentials would make little impression in these categories of assessment.

All of this came to mind as I read through the classified section of this week’s issue of the ecclesiastical newspaper. My eye was drawn to an advertisement from my home diocese, the See of Blackburn. A creation of William Temple, consisting of parishes carved out of the rapidly growing Diocese of Manchester – itself an earlier Victorian offspring of the Diocese of Chester. The ad that caught my eye had a headline in a style not uncommon in The Church Times:

I pondered whether this was the same God responsible for the creation of the universe. That is, the entire reality identifiable from earth, which is at least 28 billion light years in diameter. The God who predates time and will draw time to a close. That God? I imagine that this God probably has rather a lot to do but, God being God, perhaps there would be an infinite supply of time so that spending a few minutes reviewing the needs of the Blackburn Archdeaconry wouldn’t be too onerous.

However, wouldn’t it be more honest and meaningful to ask: ‘Do you want to be the Archdeacon of Blackburn?’ Shouldn’t our desires be material to the concept of vocation, rather than being cast into doubt under a pall of implied sanctity. Perhaps it would lead to much greater honesty and candour if we explored the motivations of why anyone wants any particular role. As the Church of England struggles to address the abuse that has happened, and is happening, in situations where piety has been asserted and manipulated, it might produce a better culture if we began with a humble recognition of our own wants and needs. Wants and needs where, in various ways, God is already present and active. Teasing these out may be the best way to achieve greater honesty; self-knowledge; deeper discernment; and a safer Church.

Perhaps spiritual directors should run the C of E – they are the people, usually, who cut through the flummery and ask this kind of inconvenient question. Might God be calling any of them to Blackburn – or even to Canterbury?