It is approximately 4½ years since COVID first appeared. I am unconvinced that any of the hard work required in order to learn lessons from a profoundly difficult experience has taken place. I’m not referring to the various national inquiries that are underway, but to the more everyday reflection which generates learning and change. It would appear, as soon as we possibly could, we were desperate to return to the world we inhabited prior to 2020. All the rhetoric of care and compassion that sprouted during the darkest days of COVID-19 seemingly vanished as quickly as it came.

For the world, the effects of COVID were not as devastating as diseases in earlier centuries. Visiting the plague village of Eyam, in Derbyshire, I was reminded about the scale and consequence of the plague. At one house in the village only a single person survived the arrival of this deadly disease, and by the time it was over she had lost 25 relatives (including in-laws). Such a degree and speed of loss is beyond comprehension. While there were a few cases of multiple COVID fatalities in a family, these are remarkably rare. For example, one family experience 4 deaths due to the virus – a truly devastating experience for the family concerned.

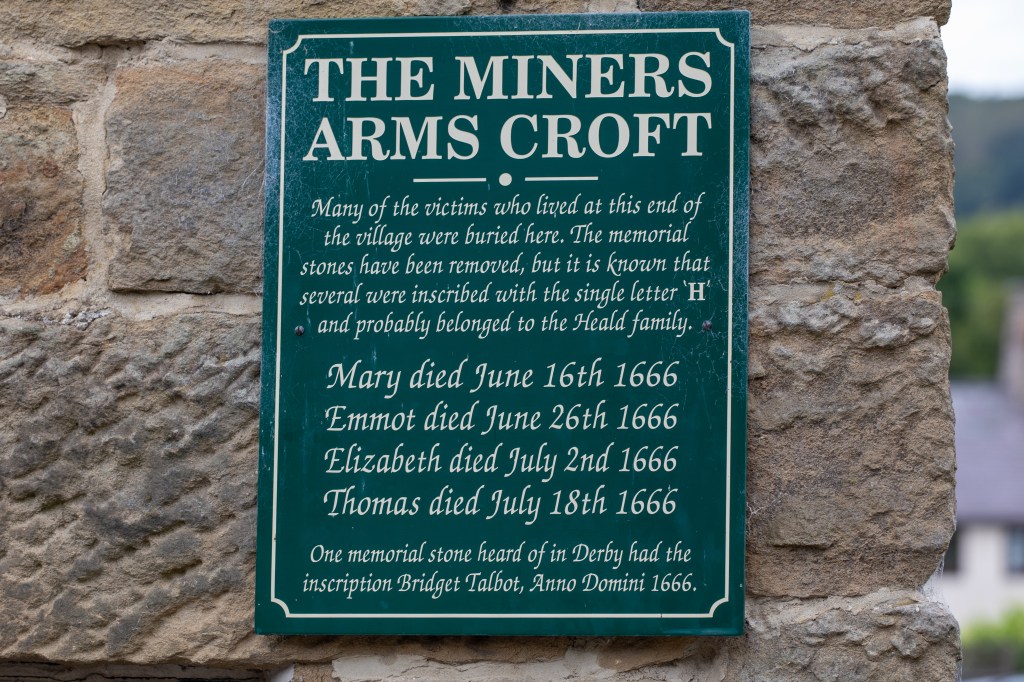

Houses in Eyam tell the grim facts of what took place in 1665 and 1666

It is more than 350 years since the village of Eyam endured a sudden and apocalyptic rise in the mortality of its inhabitants. The ability to understand what was emerging, and devise a strategy for isolation and containment, was rudimentary. It is impossible to know how many deaths the world would have seen if COVID had spread abroad in the 17th century. In the 21st century we met the emergence of the virus with rapid progress in the development of vaccines. Knowledge about society and modern communications enabled some support to be offered and applied. Yet, as the first report from the UK COVID Inquiry makes clear, there was so much more that could have been done to mitigate harm. We had, with Pythonesque thinking, prepared for the wrong pandemic.

Speaking in response to the publication of Module-1 of the COVID Inquiry, Pat McFadden (Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster), shared with Parliament his thoughts for all those bereaved by COVID. He said that: “Their grief and the nature of their loss is harrowing, with so many loved ones lost before their time”. I think that these remarks are wise and sensitive. When the Government gave daily reports about the rising number of COVID deaths there was no accompanying statistic about the number of people denied access to their loved ones immediately before, and at, the time of their death. There were no figures about those unable to attend a funeral because the numbers were restricted. The sum total of altered rituals, and final farewells denied, will never be known.

There are many more lessons-learned that will come from the COVID Inquiry. The question is, do we have the desire and appetite to absorb those lessons and make changes that will protect more infection-vulnerable communities? COVID has not gone away, and some people continue to experience very debilitating periods of illness. At the moment, at least from a media perspective, this does not appear to be on our radar.

Back in March 2020, when the scale and consequence of the pandemic were becoming apparent, the poet Simon Armitage wrote a piece reflecting on the experience of Eyam. At that stage his hopeful and poetic focus was on the task of patience, and living through COVID knowing that, inevitability, it would pass – as all pandemics do. Taking the example of Eyam he celebrates many acts of individual and collective courage, as well as personal sacrifice, which came to confer on the Derbyshire village a revered status. It is impossible to quantify the number of lives saved by the villagers’ agreement to quarantine.

“the journey a ponderous one at times, long and slow

but necessarily so”

Simon Armitage, extract from “Lockdown”

It is not easy to be patient in a time of danger and uncertainty, and understandable that those who live through it wish to forget it as soon as possible. However, the risk of doing this is that we fail to learn important lessons and reflect properly on the society in which we wish to live. Perhaps it is not too late, and the publication of further Inquiry Modules will provide a basis for us to see clearly how vulnerable people were sacrificed. Already, it has been made clear that the impact of COVID “did not fall equally”. That alone is a fact that should help us to reflect on why some groups in society are deemed to be of lesser value than others.