Recently I visited the exhibition William Blake’s Universe, in Cambridge. For many decades I have admired and enjoyed Blake’s work as both an artist and a poet. This exhibition sets Blake’s work alongside British and European Romantics who influenced his development. A review in The Guardian found this to be a weakness in the exhibition at the Fiztwilliam. Given that the space allotted is not overly large, Jonathan Jones found Blake to be overshadowed by the other artists, whose works are numerous in the gallery. This is a reasonable criticism, although I felt that the range of artists represented had its own merits – but perhaps this detracted from the ambitious title for the exhibition.

Blake is known for his paintings of vibrant angels and mythical characters. As in the way of classical painting, heavenly figures might be denoted by the presence of a halo. In the art of the Renaissance it can feel at times that the gift of a halo is a game of celestial quoits. Such paintings depict the lucky recipients of a shining disk as those rewarded for faithful and sacrificial behaviour. Often these heavenly signs shimmer and blaze with the finest gold, testimony that someone has achieved divine approval. They stand out from the canvas as the bright honorific of exceptional virtue.

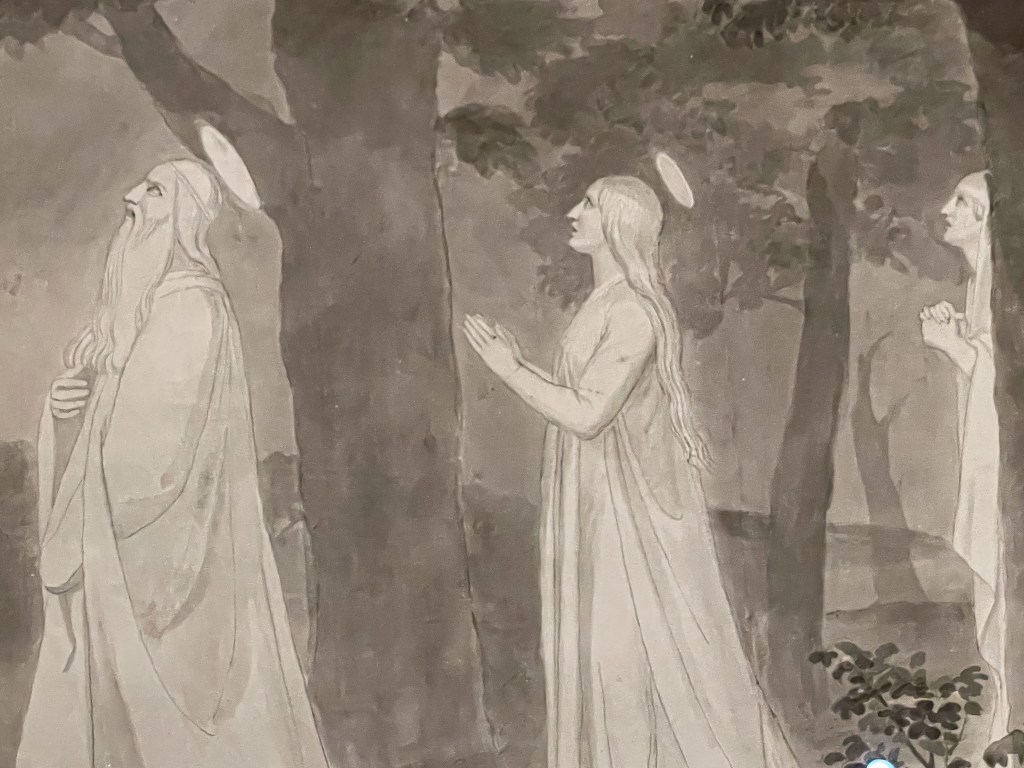

Perhaps it was due to the nature of the medium, but at the William Blake exhibition I was stopped in my tracks by a rather different impression of a halo. A key supporter of Blake during his life, the sculptor and artist John Flaxman created many mythical and Neoclassical figures. In his illustration to accompany Chatterton’s poem the Battle of Hastyngs, Flaxman depicts “Queen Kenewalcha”.

Queen Kenewalcha by John Flaxman

Looking at this painting I was struck by the depiction of the halo as an absence. It felt as though this was a gap in the paper rather than any addition of splendour. In the review of the exhibition Jones quotes Blake’s writing about the production of his books combining, as they did, both text and illustrations:

“in the infernal method, by corrosives … melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid”

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake, 1790

The halo Flaxman gives Queen Kenewalcha seems to be this kind of melting away, as though sanctity has worn a hole in the fabric of reality and allowed the underlying brightness to shine through. This halo isn’t a painstaking accretion of gold but an elliptical opening that has emerged in the life of someone who isn’t wholly captured by the beguiling surface of a reality we take for granted. Getting to the light, for the artist, becomes the act of stripping away the stuff that pleads its own importance and necessity. In this illustration, the saint is lit by this small portal of connection with a radiance which comes from the reality that is our true destiny.

“To be a human person is to be a per-sona, through whom (per-) lights and fluids, vibrations and sounds (-sonae) flow. Living in attunements, we become “resonant selves,” and being religious is to a wide extent about attuning to the reality to which we belong.”

Gregersen, N. H. (2023). “THE GOD WITH CLAY”: THE IDEA OF DEEP INCARNATION AND THE INFORMATIONAL UNIVERSE: with Finley I. Lawson,“The Science and Religion Forum Discuss Information and Reality: Questions for Religions and Science”…