The shunned, the unloved, the bleeding – the despised and the dead – were all brought back into life by Jesus. In a culture of separation and holiness-by-isolation, the Nazarite Rabbi stepped over boundaries again, and again, and again. When that culminated in the raising of a man from the dead, Lazarus of Bethany, the authorities decided enough was enough. It was time for Jesus to go away. Better that one man should die than the nation perish. Utilitarian arguments often win the day, they are beguilingly simple and often easy to implement. Focused on what is obvious and immediate, they frequently omit or deny wider truths and bigger themes that are, perhaps, simply too inconvenient to contemplate.

Like the sower’s seed, or the prodigal’s father already upon the road, the resurrections of Jesus are strewn across the Gospels. He calls back to life those who have been taught to be dead. To the contamination of a bleeding woman who dares to touch him, a wretched life is made whole. Many are healed and the doubting are allowed to walk away. At a meal with his disciples a woman dares to waste the fragrance of rich perfume; anointing the feet beside which the barren branches bring forth blossom. Here is bread and water; body and blood, the words whispered to the unworthy and the hopeless: you are alive.

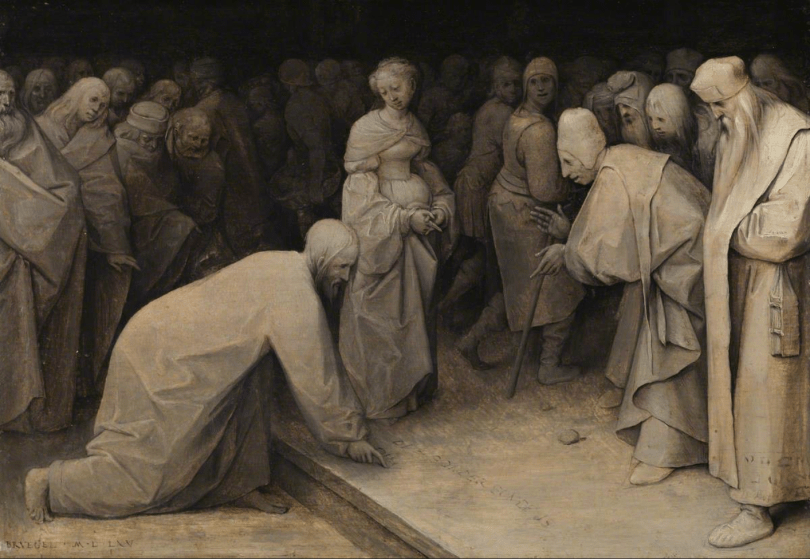

The picture at the head of this blog is called ‘Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery‘ (1565) and was painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The painting uses a technique called grisaille, meaning that it appears to be monochrome; everything is a neutral shade – sepia-like. It is hard to imagine any depiction which conveys a stronger sense of life drained away. In the crowded painting the head of Jesus is lowest of all. He writes. I have always believed that in this story, at this point, Jesus is incandescent with rage. He knows that the purpose of this moral tale is to trap him and condemn him. Did the Pharisees just happen to catch this woman in the very moment of committing adultery? Or did the lawyers’ question come first, and a cunning plan evolve to create the drama? She is caught in the act – and they know at that moment exactly where to find Jesus. He knows that those who bring her care neither for her sin nor her salvation. She is a prop. It is little wonder that this is one of very few Gospel stories where Jesus pauses and takes his time, perhaps to marshal his feelings before speaking.

“The stone-throwers walk away, one by one, according to age. Until the kneeling Christ and the standing woman remain, in an awkward reversal of their established sexual status. He tells her to go, to sin no more, to pass from this narrative, and out of our knowledge”.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/sep/30/picture-this-iain-sinclair-bruegel?CMP=share_btn_url

The teachers and the crowd are dismissed by their recognition that no one is without sin. In this dismal tale of exploitation the one whom Christians claim has no sin does not pick up a stone. Violence is interrupted and a word of resurrection love is spoken: I do not condemn you. Like the woman at the well, she stands with Jesus alone. Another woman made the recipient of easy male judgement. The choreography of sin and punishment is cut short by someone who has no interest in this kind of dance. It is time for it all to stop.

On Good Friday we are supposed to think about the agony and suffering of Jesus, and so we should. But the resurrections continue, even on the cross. For the criminal who puts his faith in Jesus, the promise of the life to come: today. Slowly, the light of the world is extinguished. Its remains are planted in the darkness of the sealed tomb: and we wait. Today, at Easter, resurrection triumphs over death. The task of the church is to live this resurrection and set free people so quickly judged by those keen to weigh some sins more than others. To punish those whom it is easy to judge, and hide much greater sin in the folds of wealth. The resurrections of Jesus are not good news for everyone.